The Malacca Dilemma and China’s energy security.

In November 2003, then Chinese President Hu Jintao described China’s energy situation as subject to the “Malacca Dilemma”. Hu was referring to the lack of supply line alternatives and their vulnerability to a naval blockade.

Hu Jintao said that “certain powers have all along encroached on and tried to control navigation through the [Malacca] Strait.” Clearly, “certain powers” referred to the United States and the ability of the US Navy to control the communication routes.

This issue has been debated for years both in China and abroad, while China has long sought to diversify energy sources and increase the share of renewable energy.

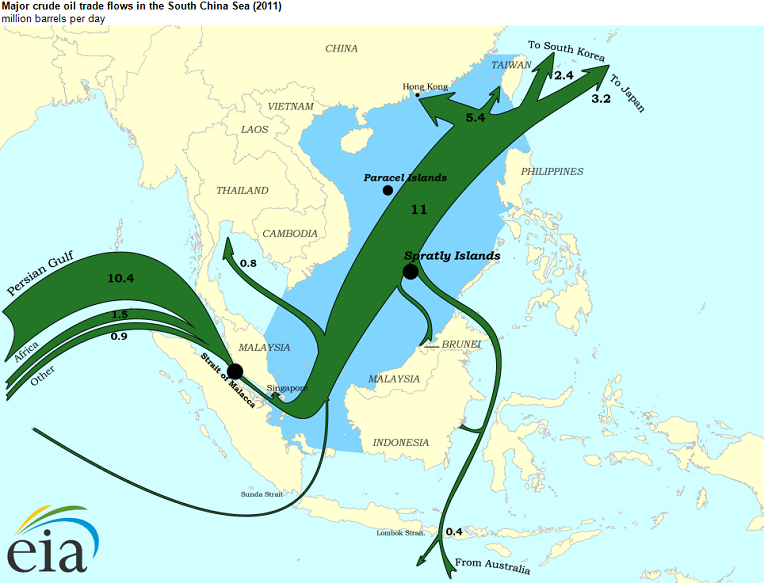

The Strait of Malacca is a narrow stretch of water between the Malay Peninsula and the island of Sumatra. It connects the Andaman Sea and the South China Sea.

It is crucial because it carries 30 to 40 percent of the world’s trade and is the shortest sea route between the Middle East and East Asia, helping to reduce transportation time and cost between Asia, the Middle East and Europe.

Its strategic location makes it a vital waterway for hydro- carbon, container and bulk cargo shipment. It carrires the second largest volume of oil in the world after the Strait of Hormuz which connects the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean.

In recent years the US policy of ‘containment’ of China and escalating American provocations over the island of Taiwan and ‘freedom of navigation’ in the South China Sea have significantly added to regional instability and to the threat of a US blockade.

Over the past two decades, the issue of sea lines of communication (SLOCs) has gained importance in China’s strategic thinking. China’s 2015 military strategy stated that “the security of overseas interests concerning energy and resources, strategic SLOCs, as well as institutions, personnel and assets abroad, has become an imminent issue.”

The document stressed that “the traditional mentality that land outweighs sea must be abandoned, and great importance has to be attached to managing the seas and oceans and protecting maritime rights and interests.” China thus sees the maritime domain as crucial to its pursuit of economic development, national sovereignty and security. US hostility to the Belt and Road Initiative is closely tied into its agenda to curtail China’s trade and economic development .

Clearly, the South China Sea (SCS) is strategically vital to China, which claims sovereignty of nearly 90% of this body of water. The full control over the SCS is fundamental to China’s capability to counter a potential US blockade.

There are alternate maritime routes, such as Sunda Strait, Lombok and Makassar Straits, but these are inferior for various reasons. The Sunda Strait is less convenient than the Strait of Malacca as it contains many navigational hazards including strong tidal flows, a live volcano, poor visibility during squalls.The Lombok-Makassar route is much safer and does not pose significant navigational hazards. However, passage along this route is longer than transit through the Strait of Malacca.

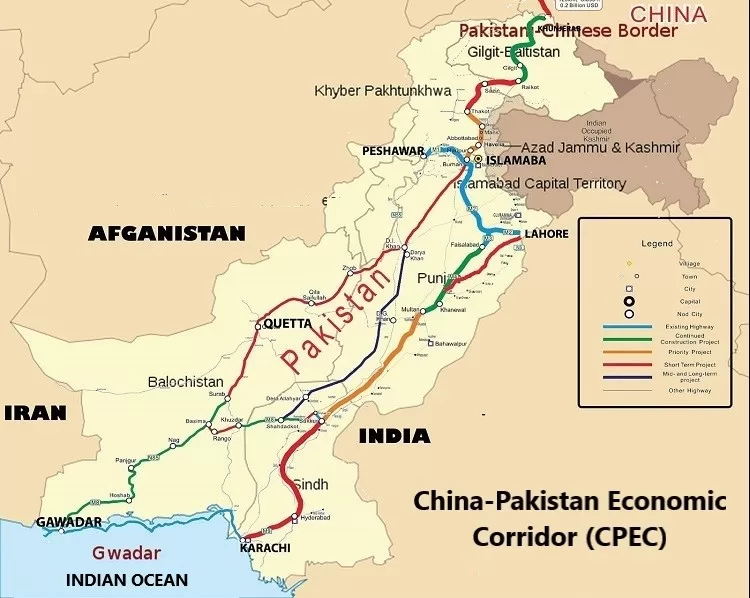

The Gwadar-Xinjiang land route, part of the $62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), is a key Belt and Road project that will allow Chinese energy imports to circumvent the Malacca Strait. However, the project is vulnerable to political instability following the recent US-backed overthrow of the Pakistan government and ongoing terrorist activities, which can potentially disrupt the supply of resources.

Chinese authorities are trying to mitigate the Malacca Dilemma by reducing dependence on energy imports from the Middle East. Beijing is trying to establish alternative land links and energy cooperation with Russia, Central Asia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Iran and Turkey. Cooperation with Pakistan through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) was perceived as an opportunity to gain an additional access point to the Indian Ocean.

The Myanmar-Yunnan oil and gas pipelines are operating right now. However, the volume of the energy resources being imported to China is not enough to fully substitute for trade through the Strait of Malacca, and ongoing conflict in Myanmar limits the investment environment.

China constantly seeks new ways to solve the Dilemma – from diversifying sources of oil and gas imports to proposing new land and sea projects. A key development in the past two years has been the major expansion of energy trade with Russia. This is not new, as China has been Russia’s largest trade partner of the past 13 years, but notably Russia has now surpassed Saudi Arabia as China’s primary source of oil imports. In 2021 China became the world’s largest importer of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG), overtaking Japan.

At the beginning of February 2023, China and Russia significantly strengthened of cooperation in the energy sector, with major oil and gas corporations from two nations signing new deals worth $117.5 billion. Chinese President Xi Jinping in his meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Beijing on 4 Feb 2022, emphasized that the two countries should steadily advance major oil and gas cooperation projects and strengthen joint innovations in energy technologies, adding that both countries should support each other in ensuring energy security.

China-Russia energy cooperation has advanced steadily over the past 12 years. In 2011 and 2018, the first and second lines of China-Russia crude oil pipelines were successively put into commercial operation. These lines have since enabled a capacity of 30 million tonnes of crude oil to be imported into China each year. In 2019, the China–Russia East-Route natural gas pipeline went into operation, setting a new milestone for energy cooperation between the two countries.

Sources:

- China Monitor, https://shorturl.at/CDGLP

- CGTN, 04-Feb-2022. https://news.cgtn.com/news/2022-02-04/Xi-calls-on-China-Russia-to-strengthen-cooperation-in-energy-17nUKB9Jsas/index.html

- CGTN, 05-Feb-2022. https://news.cgtn.com/news/2022-02-05/China-and-Russia-ink-new-deals-on-energy-cooperation–17psVBDce8E/index.html

- Asia Deep Dive, 12 Aug 2023. ‘What is the Malacca Dilemma?’ https://www.facebook.com/sasha.gervais/posts/pfbid0kccoVjrGJ1uR7qoWvbyLT9dyqCgPCBUFLZFnr3oCeRKZkiJ7frRvYaKtgdafKg9rl