Over 20 more countries apply to join the now 10 member BRICS+ group.

From 1 January 2024, the existing five member BRICS group (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) grew to become BRICS PLUS, with the addition of five new members – Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

BRICS Ambassador at large, South Africa’s Anil Sooklal, has revealed that there is a huge demand from developing countries to be inducted into BRICS in 2024. Sooklal is reported as stating that a further 20 countries, in addition to the recently admitted five new members invited in August 2023, have applied to join the BRICS group. In discussing South Africa’s Presidency of the 15th annual BRICS Summit, in late November 2023 he stated that:

“Over 20 countries have formally applied to join BRICS, while the same number have expressed interest. This is affirmation that BRICS is playing an important role in championing emerging and developing economies. There are a large number of interested parties and these will be dealt with by the respective Foreign Ministers.”

(Ambassador Anil Sooklal)

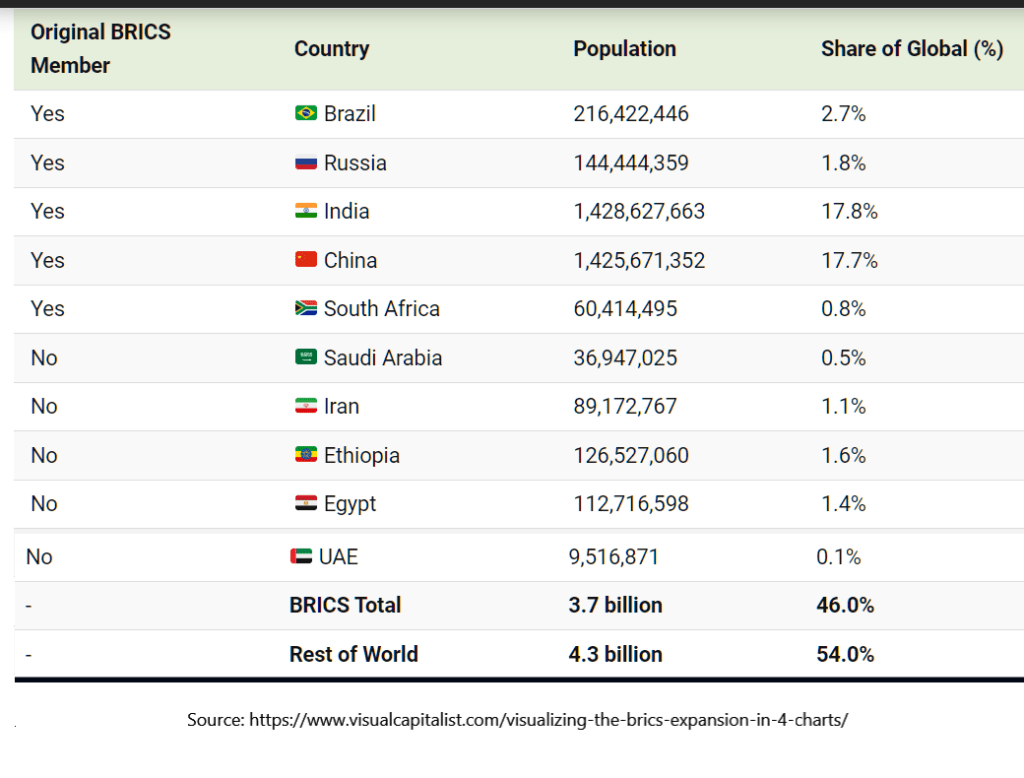

BRICS Share of Global Population

BRICS has always represented a major chunk of global population thanks to China and India, which are the only countries with over 1 billion people.

The two biggest populations being added to BRICS are Ethiopia (126.5 million) and Egypt (112.7 million). See the following table for population data from World Population Review, which is dated as of 2023.

The BRICS-10 account for over 45% of the world population. Adding potential new countries to BRICS, such as Indonesia (277.5 million), Pakistan (240.5 million), Nigeria (223.8 mllion), Bangladesh (223.8 million) and Vietnam (98.9 million) would add another 1.1 billion people to BRICS, representing 60% of the world’s population.

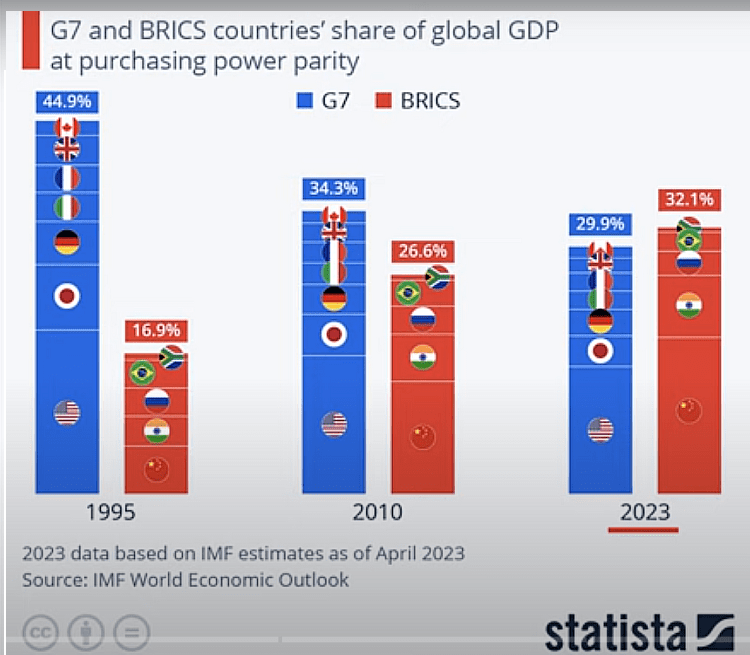

BRICS Share of Global GDP

In contemporary macroeconomics, gross domestic product (GDP) refers to the total monetary value of the goods and services produced within one country. Nominal GDP calculates the monetary value in current, absolute terms. Real GDP adjusts the nominal gross domestic product for inflation.

Some accounting goes further, adjusting GDP for purchasing power parity value (PPP). This adjustment converts nominal GDP into a number which allows comparison between countries with different currencies.

The original six BRICS members were expected to have a combined gross domestic product (GDP) of $27.6 trillion in 2023, representing 26.3% of the global total. With the new members included, expected GDP climbs slightly to $30.8 trillion, enough for a 29.3% global share.

However, using GDP (PPP) or gross domestic product based on purchasing power parity yields a more realistic result. Purchasing power parity is a macroeconomic analysis metric used to compare economic productivity and standards of living between countries.

The World Bank releases periodic reports that compares the productivity and growth of various countries in terms of PPP and U.S. dollars. Both the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) use weights based on the PPP metric to make predictions and recommend economic policy.

The following chart (based on IMF analysis) compares GDP (PPP) of the original BRICS economies with the G7 economies. It can be seen that by 2023 the G7 countries’ share of global GDP (PPP) was 29.9%, compared to the original five BRICS countries’ share was 32.1% – ahead of the G7 Group.

The 20 New BRICS Candidate Countries

In terms of the 20 new candidates, what will be attractive to many is the fact that the BRICS does not insist upon formal trade negotiations and the permanent imposition of tariff reductions. Rather than a defined tariff reduction regime, the BRICS has a far looser approach. This removes political barriers that include insistence on market and political reforms, which is more of a Western approach, and also means that tariff reductions and trade development enhancements can be implemented on an as-need basis. These are fundamental points of interests to emerging economies who may otherwise struggle to compete with cheap imports. It also allows more autocratic regimes to participate without the need to introduce unwelcome reforms that may not be considered in their national interest. Most of the 20 applicants have not been publicly identified, however in my experienced opinion are likely to include the following.

- Afghanistan. An outlier, but has significant resources and is a member of the BRI. Diplomatic changes are required, but China, India and Russia are all keen to see redevelopment in the country once political stability can be secured.

- Algeria. In terms of market size, it has the tenth largest proven natural gas reserves globally, is the world’s sixth-largest gas exporter, and has the world’s third-largest untapped shale gas resources.

- Bangladesh. It is one of the world’s top five fastest growing economies and is undergoing significant infrastructure and trade development reforms. It shares a 4,100 km border with India.

- Bolivia. Asset-rich but relatively poor, it has the fastest GDP growth rate in Latin America.

- Cuba. Its defiance of sanctions has long made it a favorite of China and Russia when wanting to annoy the United States. It also has significant agreements with China and Russia, is a member of the BRI and has significant Caribbean and LatAm influence.

- Ecuador. It is negotiating Free Trade Agreements with both China and the Eurasian Economic Union. It would make sense to substitute these with a looser BRICS arrangement.

- Indonesia. One of Asia’s leading economies, its potential has again been raised to join BRICS. In July 2023, Jakarta accepted an invitation to participate in the 2023 BRICS summit.

- Kazakhstan. Its economy is highly dependent on oil and related products. In addition to oil, its main export commodities include natural gas, ferrous metals, copper, aluminum, zinc and uranium.

- Mongolia. It s both a problem and solution, while geographically attractive. It requires extensive investment in its energy sector; yet is resource-rich and a transit point between Russia, Kazakhstan and China. It is not a member of any trade bloc, with a looser BRICS arrangement better suited to maintaining its regional impartiality.

- Nicaragua. It is a mining player and the leading gold-producing country in Central America. It has a Free Trade Agreement with the ALBA bloc, and is an influential player in the Caribbean.

- Nigeria. Its Foreign Minister has announced that the country intends to become a member of the BRICS group of nations within the next two years. Nigeria has the largest population in Africa and a GDP of US$448 billion, a population of 213 million and a GDP per capita of US$2,500. It has the world’s 9th largest gas reserves and significant oil reserves.

- Pakistan. It has filed an application to join the BRICS group of nations in 2024 and is counting on Russia’s assistance during the membership process, the country’s newly appointed Ambassador to Russia has stated.

- Senegal. It is a medium capacity gold mining and energy player, with reserves in gold, oil, and gas. The energy industry is at a growth stage as reserves have only recently been found. The energy-hungry BRICS nations will be keen to secure its supplies.

- Sri Lanka. It isn’t keen on opening up its markets yet has significant economic problems. China is interested in port and Indian Ocean access while Russian tourism investments are increasing. A BRICS agreement would be loose enough to satisfy all concerns, while India will want to keep an eye on it.

- Sudan. Its top five export markets are 100% BRICS – China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, India, and the UAE. Sudan also has regional clout. It is Africa’s third-largest country by area, and is a member of the League of Arab States (LAS). Should Sudan join the BRICS it would give the group complete control of the Red Sea supply routes.

- Thailand. It is one of ASEAN’s largest economies, via ASEAN it has additional Free Trade Agreements with Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, China, Hong Kong and India, and agreements with Chile, and Peru. Thailand is also a signatory to the RCEP FTA between ASEAN and Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea.

- Turkiye. Its trade figures with the current and most of the upcoming BRICS members show significant growth. Getting access to BRICS NDB funding may also prove attractive for Ankara as talks are expected across a number of issues.

- Uruguay. It has joined the BRICS New Development Bank – a sure sign that official BRICS membership is pending.

- Uzbekistan. It is one of Central Asia’s fastest growing economies, yet it is hampered by being double-landlocked. Membership of BRICS would give it market access to China, Europe, and the rest of Asia in a more protected manner.

- Venezuela. Another outlier, but its energy reserves and political stance fit well with China and Russia’s needs.

- Additional candidates are also likely to include Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, Chile, Peru, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Vietnam, Cameroon, DR Congo, Kenya and Tanzania among others.

Summary

At first glance this may appear a disparate and disjointed group with little in common. Yet this is part of the appeal. In the West, trade partner economies are typically viewed in terms of economic capability, and their immediate usefulness (or otherwise) to Western economies. Emerging economies that show promise are often ‘encouraged’ to embark on political and economic reforms to ‘bring them to international standards’. What has become apparent is that this tends to mean ‘Western benefits’ take precedence over these economies. That has included inadvisable World Bank loans, and the imposition of US dollar and Euro trade at the expense of their sovereign currencies.

In gathering together the ‘developing’ or ‘emerging’ economies, the BRICS have taken a bet on the future. While some potential members may fall into future difficulties created by regional conflicts, most will not. Absorbing these new members will take time – but could be completed by 2030.

Closer examination also reveals that many of the 20 listed above are significant economies, often amongst the leading players within their own respective trade blocs. These include the Greater Arab Free Trade Area (GAFTA), Latin America’s Mercosur, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), and ASEAN, amongst others. Having BRICS members inserted into these regional blocs significantly enhances the BRICS own reach and influence within them. By comparison, the European Union appears strictly rigid in its approach. It resembles a closed market rather than an open one. In this way, the BRICS can be seen as an antidote to the previously over-regulated Western trade group systems, where trade negotiations are measured in decades and political conditions imposed in return for Western market access.

What is happening instead is far more revolutionary, and is leading to a rather more considered, and inclusive multi-lateral approach. The BRICS movement is developing more as a trade philosophy than a specific bloc – and will pave the way ahead in terms of global trade flows well into the coming decades.

Source: BRICS Information Portal, December 19, 2023. http://infobrics.org/post/40089/.

Author: Chris Devonshire-Ellis