The industrialization of agriculture by capitalism and Metabolic Rift.

The industrialization of agriculture in the nineteenth century rested upon the long historical emergence of capitalism as a distinct socioeconomic order.

An extract from Capitalism and Robbery: The Expropriation of Land, Labor, and Corporeal Life, by John Bellamy Foster et al, Monthly Review, Dec 01, 2019. See also: The review of Guano and the opening of the Pacific world, recently shared by China Environment.

*********************

Marx presented a systematic analysis of how industrialized agriculture robbed the land of necessary nutrients. He recognized and provided the basis for assessing the interlocking oppressions and processes of expropriation that accompanied this soil crisis. Nutrients from the countryside accumulated as waste in the cities and were washed away to sea as part of urban refuse. A variety of means were sought to replenish the land. In particular, between 1840 and 1880, an international fertilizer trade was established, shipping millions of tons of guano and nitrates from Peru and Chile to the Global North. The mining of guano was largely rooted in expropriation of land, labor, and corporeal life, all of which were necessary to make this fertilizer so profitable. Initially male convicts and slaves worked as forced labor on the guano islands, using picks, shovels, wheelbarrows, and sacks. As the availability of slaves declined, Chinese workers were imported as part of the “coolie” labor system.

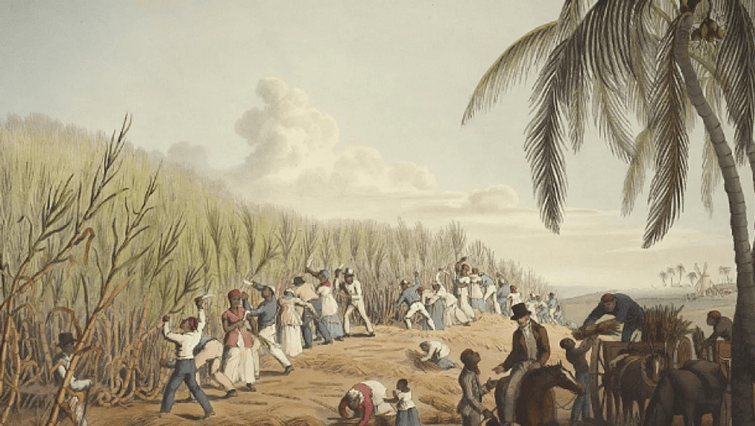

The industrialization of agriculture in the nineteenth century rested upon the long historical emergence of capitalism as a distinct socioeconomic order. As Beckert details in the Empire of Cotton, “imperial expansion, expropriation, and slavery” were critical to its formation.29 Throughout the age of mercantilism, from the mid–fifteenth to mid–eighteenth centuries—a period Beckert refers to as “war capitalism”—earlier property forms and productive relations were dissolved via the enclosure of the commons and imperialism, formally transferring title of land to the bourgeois class. The racialized characteristics of capitalism were embedded from the start as Africa, Asia, and the Americas were colonized while genocidal campaigns were waged against indigenous peoples and Africans were enslaved to work on plantations.30 These conditions contributed to the massive transfer of wealth to England and other European nations. Marx explained that this process of primary expropriation was pivotal to the English Industrial Revolution.31 Cotton was associated with the robbery of nature and nonwaged labor, as well as the exploitation of waged labor, providing the cheap materials essential to the rising textile factories, where industrial laborers subsisted on imported potatoes from the increasingly exhausted fields of Ireland.

The First Agricultural Revolution in the capitalist age coincided with the enclosures, from the late fifteenth to early nineteenth centuries, and the formal transfer of land titles. Peasants and small land holders were driven from the land, pauperized, proletarianized, and forced to sell their labor power for wages to purchase the means of subsistence. These changes ushered in a heightened alienation from nature, a more distinct town-country division, and specialized food and fiber production. The Second Agricultural Revolution, from 1830 to 1880, was characterized by the development of soil chemistry, the growth of the fertilizer trade and industry, the increase in the scale and intensity of agricultural production, and “land” improvements, such as imposing uniformity across fields, making them easier to apply modern technologies. Additionally, intensified agricultural production required massive fertilizer inputs in order to enrich the soil.32 In numerous ways, this period is the embodiment of appropriation without equivalent and without reciprocity.

Liebig played a pioneering role in studying the changing soil chemistry in relation to the advancing capitalist industrial agriculture. He noted that the production of crops depended on the soil containing essential nutrients—such as, but not limited to, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. He explained that a rational system of agriculture must be governed by the “law of compensation” or the law of replacement.33 The nutrients that are absorbed by plants as they grow must be restored to the soil to support future crops. But this was far from the case in Western Europe and the United States in the nineteenth century. Liebig noted that the British high-farming techniques constituted a “robbery system,” leading to the despoliation of the soil.34 Marx, who studied Liebig’s work, detailed how the application of industrial practices to increase yields and the transportation of food and fiber to distant markets in cities were generating a rift in the soil nutrient cycle. In Capital, he famously observed that capitalist agriculture progressively “disturbs the metabolic interaction between man and the earth,” preventing the “return to the soil of its constituent elements consumed by man in the form of food and clothing; hence it hinders the operation of the eternal natural condition for the lasting fertility of the soil.” As a result, “all progress in capitalist agriculture is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the worker, but of robbing the soil; all progress in increasing the fertility of the soil for a given time is progress towards ruining the more long-lasting sources of that fertility.”35

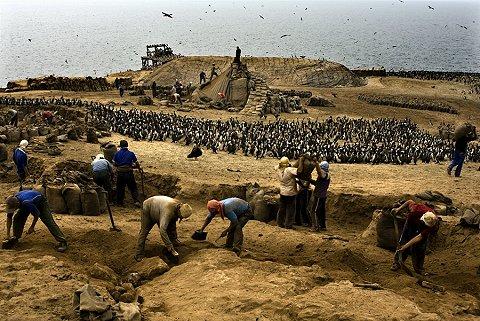

Marx thus presented a systematic analysis of how industrialized agriculture robbed the land of necessary nutrients. But he also recognized and provided the basis for assessing the interlocking oppressions and processes of expropriation that accompanied this soil crisis. As the nutrients from the countryside accumulated as waste in the cities or were washed away to sea as part of urban refuse, a variety of means were sought to replenish the land.36 In particular, between 1840 and 1880, an international fertilizer trade was established, which involved shipping millions of tons of guano and nitrates from Peru and Chile to the Global North. The mining of guano was largely rooted in expropriation of land, labor, and corporeal life, all of which were necessary to make this fertilizer so profitable. Initially male convicts and slaves worked as forced labor on the guano islands, using picks, shovels, wheelbarrows, and sacks. As the availability of slaves declined, Chinese workers were imported as part of the “coolie” labor system.37

Former slavers used coercion, deceit, kidnapping, and questionable contracts to set up this new racialized regime of bonded labor, which supplied workers for colonies and former colonies throughout the world. Over ninety thousand Chinese workers were shipped to Peru during the heyday of the guano trade—approximately 10 percent died in passage due mainly to poor treatment and malnourishment. The most unfortunate unfree laborers were sent to the guano islands, where the total workforce fluctuated between two hundred to eight hundred workers at any given moment, but where lives were used up rapidly—considered of less value than the guano that they dug up.38 Only men were sent to these islands, where over “one hundred armed soldiers” kept guard, preventing workers from committing suicide by running into the ocean.39 Marx described this “coolie” system as a form of “disguised slavery.”40 Eye-witness accounts noted that these Chinese workers were treated as expendable, regularly flogged and whipped if they did not fulfill the demanding work expectations. They labored in the hot sun, filling sacks and wheelbarrows with guano, which they then transported to a chute that loaded the boats. Guano dust coated their bodies and filled their lungs. The smell was overwhelming. One account described the conditions as “the infernal art of using up human life to the very last inch,” as the lives of the workers were very short.41 Several British shipmasters were “horrified at the cruelties…inflicted on the Chinese, whose dead bodies they described as floating round the islands.”42

Here we see how expropriation works at the boundaries of the capitalist system. Guano, which had been used for thousands of years to enrich the fields of Peru, was quickly being exhausted to replenish the fields of the Global North. The sea birds that deposited hundreds of feet of guano on the islands were often killed, as they were deemed a nuisance to extractive operations. Guano was being removed at a much faster rate than it accumulated. The new racialized labor system that was imposed was largely predicated on brutally expropriated bonded labor, enhancing accumulation at the core of the system. The conditions resulted in a corporeal rift, which undermined living conditions, leading to poor health and an early death for many of the workers, who were simply replaced by other imported laborers. All of this, moreover, was meant to make possible a continuation of a robbery system where the soil in Europe and North America was being systematically robbed of its nutrients.

These conditions of expropriation were a central component of supporting the Second Agricultural Revolution accompanying the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution, in which cotton was so integral, had been based on the triangular slave trade. It was after the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, which formally abolished slavery within most British colonies, that the British turned to the “coolies” from Asia, a disguised form of slavery as a way of replacing open slavery, with new forms of bonded labor. Guano, in this sense, was part of a second triangular trade, geared to the industrialization of agriculture, British high farming, and the need to restore the impoverished soil by means of an imperial system, involving the worst extremes of labor exploitation and the expropriation of corporeal life.

In the nineteenth century, women were at the center of the Industrial Revolution, constituting the majority of the core industrial workforce in England, especially in the cotton, silk, wool, and lace sectors of textile production.43 Marx took detailed notes regarding their positions within the workforce and the conditions under which they labored. Along with Engels, he documented the specific types of hazards that these women were exposed to, which created an array of health problems that shortened their lives, such as respiratory issues from inhaling fibers. Both working-class men and women experienced forms of corporeal degradation associated with their working conditions, but the specifics varied according to the types of work in which they were concentrated.44 Additionally, women received much lower wages than men and had a disproportionate responsibility for social reproductive work to support whole families, to the extent that this additional activity was possible, given the long working hours.45

Women in this period were superexploited in the industrial workforce, producing a large share of surplus value in factories, while at the same time they were compelled to produce use values, which served as a free gift to capital, through their work in the home in the process of reproducing labor.46 Under these conditions, which threatened the very existence of the working-class family, women, though responsible for the social reproduction of the family and the labor force, could scarcely maintain their own existence. The double day was not a creation of late capitalism, but rather was present at the very birth of industrial capitalism—at a time when the working day (including the time necessary to get to and from work) for women was often twelve hours or longer, six days a week.

For the working classes, wage exploitation was also in a sense nutritional exploitation, as wages were mainly expended on the most basic foods necessary for survival. Intensive agricultural production in England, which was supported by imported fertilizer, contributed to the creation of a new international food regime after the Irish potato famine and the end of the Corn Laws in 1845–46. What Marx himself called the new food regime involved a shift toward more of a meat-based system, in which additional land was being devoted to animal production, geared to serving the upper classes.47 In contrast, as Marx and Engels detailed, the working class subsisted on poor-quality and inadequate diets, consisting largely of bread and very few vegetables.48 To make matters worse, the food, drink, and medicine that was available was adulterated, containing a vast array of contaminates, such as mercury, chalk, sand, feces, and strychnine. Regular consumption of these materials contributed to various health ailments, chronic gastritis, and death. Women tended to be the most malnourished, as they consumed less food and ate last within families. Conditions were worse in England’s colony of Ireland, which was forced to export its soil (nutrients) and its capital to England.49

The industrialization of agriculture was intimately connected to the transgression of natural limits, given the interlocking expropriation of land, labor, and corporeal life that shaped the social metabolism and that constantly expanded capitalism’s intensive creative destruction. The new system required the exponential growth of external inputs from the environment. Metabolic rifts, the imperial draining of wealth from the Global South, and a system of exploitation that had expropriation as its background condition defined the rise of capitalism in the nineteenth century.

Nauru was heavily mined for guano

Notes: See original Monthly Review article for footnotes, etc.

monthlyreview.org/2019/12/01/capitalism-and-robbery/