In commemoration of China’s greening progress

By Kelvin Kwok May 16, 2021. Originally posted in K in the Clouds blog; Shared on 17 May 2021 to Xi Jinping: China’s Exceptional President group on Facebook ( https://www.facebook.com/groups/688430344583422/posts/4066311076795315 )

It takes more than “HOW DARE YOU” to restore and preserve nature. It is not just a childhood, we are talking about GENERATIONS.

Below, let us take a look at how the Chinese spent the last 70 years trying to paint China green again.

There are countless mega projects being conducted in China, but one category stands out. Projects in this category do not have a fixed site. They can be seen everywhere from deserts deep in the northwest to the coastline the southeast.

You may have heard of some of them, such as the Three-North Shelter Forest Programme (三北防护林工程) and the Natural Forest Protection Project (天然林保护工程). There are also the Beijing-Tianjian Sandstorm Source Control Project (京津风沙源治理工程), as well as the Returning Farmland to Forest Project (退耕还林工程), Returning Livestock Pastures to Natural Grasslands Project (退牧还草工程), and many more.

They are collectively known as the Land Greening (国土绿化) projects.

Instead of having steel as the basic ‘building block’, they use something far softer — grass and wood.

(photo: 飞翔)

(photo: 张德刚)

They have caused a lot of controversy, as they are far from perfect and are not even close to completion. In fact, there is no ‘completion date’ for them, but only endless cycles of exploration, implementation and improvement that take generations of effort.

(photo: 视觉中国)

In 1949, the forest cover rate in China was estimated to be only around 8.6% – 12.5%. Yet by the end of 2018, this had already reached 22.96% according to data from the 9th National Forest Resources Inventory, which translates into 2.2 million square kilometres of forest areaOver the past 70 years, the net growth of forest area in China is enough to cover the entire Xinjiang. The growth in China’s forest resources is also the largest and most rapid in the world during the same period.

(diagram: 巩向杰, Institute for Planets)

In addition to afforestation, grasslands spanning hundreds of thousands of square kilometres undergo yearly maintenance including grass planting, enrichment and fencing. Every single tree and grass has helped paint the vast land of China green.

(photo: 沈龙泉)

That we can live in a China increasingly rich in vegetation is a direct consequence of the uninterrupted Land Greening projects.

At some point one needs to ask, what was the cause for all these changes? And how were they made?

1. The vast land

The continuous rising of Tibetan Plateau for tens of millions of years had transformed the landscape of the eastern regions of Asia. Due to the presence of this natural barrier, an arid zone appeared in the northwestern inland of China, which gradually turned into a large barren desert.

A desert composed of sand is known as sandy desert. In China, sandy deserts cover an area of 588,000 square kilometres, which accounts for 6.1% of the entire land area of country.

(photo: 蒋涛)

Deserts with mostly stones and gravels are known as gobi. They always accompany sandy deserts and are distributed in their upstream. Gobi terrains span 928,000 square kilometres in China, occupying 9.6% of all land area.

(photo: 刘白)

Over the past hundreds of thousands and up to millions of years, the global climate had gone through alternating dry and humid periods as well as temperature fluctuations. This catalysed the birth of Mu Us, Hunshandake, Khorchin and Hulunbuir, together known as China’s Four Sandy Lands, in the northern semi-arid and semi-humid regions.

(photo: 陈剑峰)

During the last one hundred thousand years, human activities in addition to climate fluctuations further accelerated and expanded the scale of land surface desertification.

(photo: 李滨)

In recent centuries, humans have done excessive reclamation, grazing and logging. This resulted in extensive deforestation and turned large amount of grasslands into farmlands.

(photo: 李贵云)

During the establishment of the New China, people in the older generations were faced with an exhausted land and a basket of ecological problems.

The first and foremost problem was desertification and sandification. According to the 5th National Desertification and Sandification Monitoring, desertified land covered an area of 2.61 million square kilometres, accounting for 27.2% of all land area in China. There was also 1.7212 million square kilometres of sandified land.

Yellow: sandy lands (沙地)

Orange: gobi lands (戈壁)

Brown: saline-alkali lands (盐碱地)

(diagram: 巩向杰, Institute for Planets)

As the land degrades, soil turns into sand, which joins force with the wind to form sandstorms that corrode away more farmlands and pastures while burying railways and highways.

(photo: 邱会宁)

The second problem was soil erosion, which is a consequence of wind and water eroding the land surfaces that lack vegetation. Based on the findings of dynamic monitoring of soil erosion, 2.7369 million square kilometres or 28.4% of land area was affected in China.

Green: wind erosion (风力侵蚀)

Blue: water erosion (水力侵蚀)

Purple: freeze-thaw erosion (冻融侵蚀)

Darker colour indicates higher severity

(diagram: 巩向杰, Institute for Planets)

In the North China and northwest regions, barren slopes were scoured by seasonal concentrated precipitation, leaving behind precipitous valleys where vegetation cannot take root at all. This greatly impacted daily lives and travelling for the locals and severely hindered economic development in the region.

(photo: 任世明)

Sediment coming from the upstream of Yellow River led to siltation in the downstream and consequently devastating floods.

(photo: 邓国晖)

There were additional problems like soil salinisation, rocky desertification and sharp decline in biodiversity, among others. All of these presented an enormous challenge for human survival and development.

(photo: 刘广辉)

In the face of dire ecological problems and absolute poverty affecting hundreds of millions, the Chinese government rolled out the one crucial policy — Land Greening.

And the very first battle in this grand war of motherland greening started right in the most destitute area.

2. Pioneers at the sea of sand

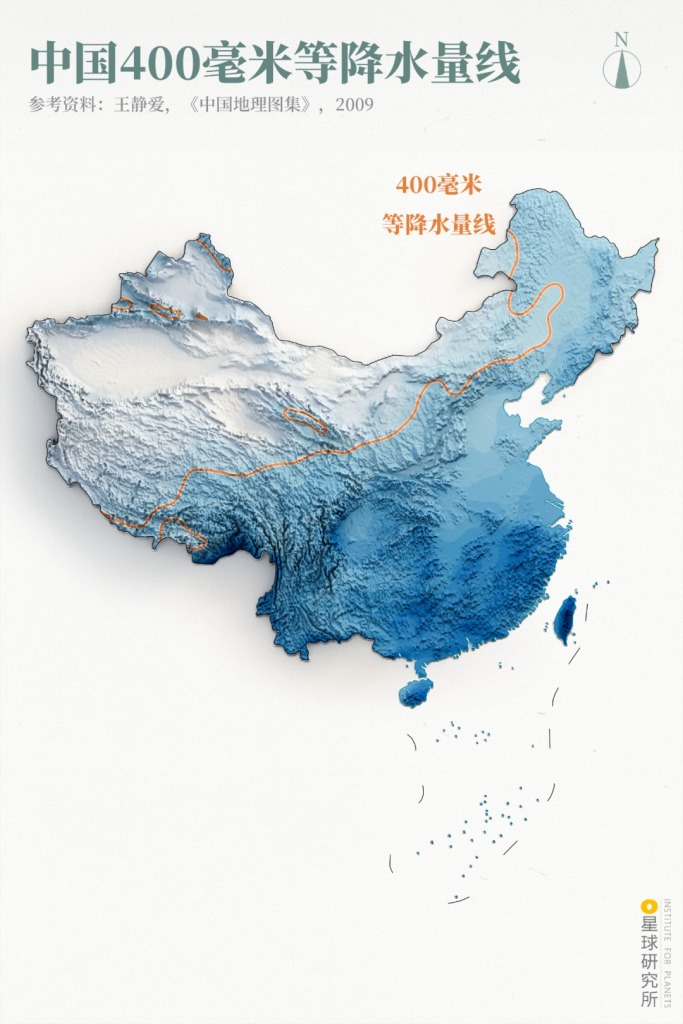

There exists a line, an invisible one, that sprouts from the northeast of China. Starting from Hulunbuir, it stretches southward along the Greater Khingan Range and winds past the Yan Mountains, Northern Shaanxi and southern parts of Gansu and Ningxia, all the way to and through the Tibetan Plateau. This line, known as the 400-millimetre isohyet, draws the border between the dry world and the wet world.

(diagram: 巩向杰. Institute for Planets)

Anywhere to the west and north of this line is all but arid and semi-arid zones where sandstorms rage on a regular basis. This front is where windbreak and sand fixation forests, the ‘first echelon’ of the Land Greening troops, are stationed.

Back in 1954, in order to connect the North China Plain and the northwest, engineers started planning a railway between Baotou in Inner Mongolia and Lanzhou in Gansu, later known as the Baotou-Lanzhou Railway. One issue they had was that this route has to pass through the Tengri Desert 6 times, meaning that more than 40 kilometres of rail would be completely exposed to the desert environment, plus there would be sand hills 10-30 metres high along the Shapotou section in Ningxia looming right above the slender rail.

(photo: 刘伟钐)

Protecting the railway from sand erosion was thus of utmost importance. However, the forever moving sand dunes made it impossible to plant any vegetation.

Was there a way to fix the sand?

Soon after the founding of New China, the Chinese Academy of Sciences established a desert research station in the heartland of Shapotou. After several years of experimentation with the assistance from Soviet experts, researchers finally found the secret to sand fixation — grass grid.

(photo: 小强先森)

To make a grass grid, one has to gather wheatgrass or the stem of other plants, fold and insert them half way into the sand. Keep on and make quadrats of 1 metre long and wide, then weave a net with arrays of grass quadrats.

(photo: 视觉中国)

Sand carried in the wind gets caught and stacks up within the grid network, which in turn slows down the movement of the entire sand dune.

Since most of the sand particles carried in the wind move close to the land surface, the

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

Sand and water accumulate more readily within the grass grid. Through the actions of microorganisms, the surface of sand dunes slowly form a layer of crusty skin. This facilitates the transition of quicksand that lacks water and nutrients into a fixed structure. At the same time, sandy plants seeded in the grass grid together with grass seeds brought in by the wind start to germinate and grow.

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

With that, sand is gradually fixated within the grass grid and greens start to emerge.

(photo: 视觉中国)

Grass grid sand fixation technology was rapidly spread to the entire arid zone. From along the Qinghai-Tibet Railway to the entire stretch of Taklamakan Desert Highway, and from water channels to pipe networks, grass grids can be seen tenaciously holding the sandy land in place.

Running across Yuli County in Bayingolin, Xinjiang, this is the third desert highway in the province

(photo: 视觉中国)

Building grass grids, as well as soil grids and rock grids that serve similar purposes, is only the first step to windbreak and sand fixation. To get to the root of the problem and transform desertified and sandified terrains for good, we need to a specific type of plant.

Shrubs.

Sandy plants including the hyloxylon (saxaul), tamarisk (salt cedar), ceratoides, nitraria, hippophae (sea buckthorn), salix (sandy willow) and caragana (peashrub) never looked attractive on the ground. But below the ground surface they have extremely elaborate root systems that are resistant to drought, cold and saline conditions. They are really hardy and adaptive.

(photo: 吴静)

But how should these shrubs be planted on moving sand?

Sand layers that retain water are usually buried below the surface at a depth of dozens of centimetres or even more. Therefore, digging machines are needed to deep plant these shrubs. But the job is far from done after planting, because the trace water content in these sand layers is no where close to being sufficient for proper growth of these new seedlings.

To address this, workers came up with a new watering method, widely known as drip irrigation. This method directly delivers water and nutrients to the roots of these plants while minimising loss from evaporation and seeping.

(photo: 视觉中国)

Where water is relatively abundant, arbors can be planted instead. Mountain ranges like the Tianshan and Qilian hold great mass of glaciers and accumulated snow. When these melt, streams of water merge into inland rivers including the Tarim River and Etsin Gol (also known as Heihe or ‘Black River’). They flow through deserts and replenish oases.

White poplars and desert poplars are planted in dense patches along rivers and around lakes. These taller members of the arbor can act as a barrier to break winds and fix sand.

(photo: 王毅)

Alternatively, flood channels are built so that seasonal floods can also be utilised for arbor irrigation in dry deserts.

(photo: 视觉中国)

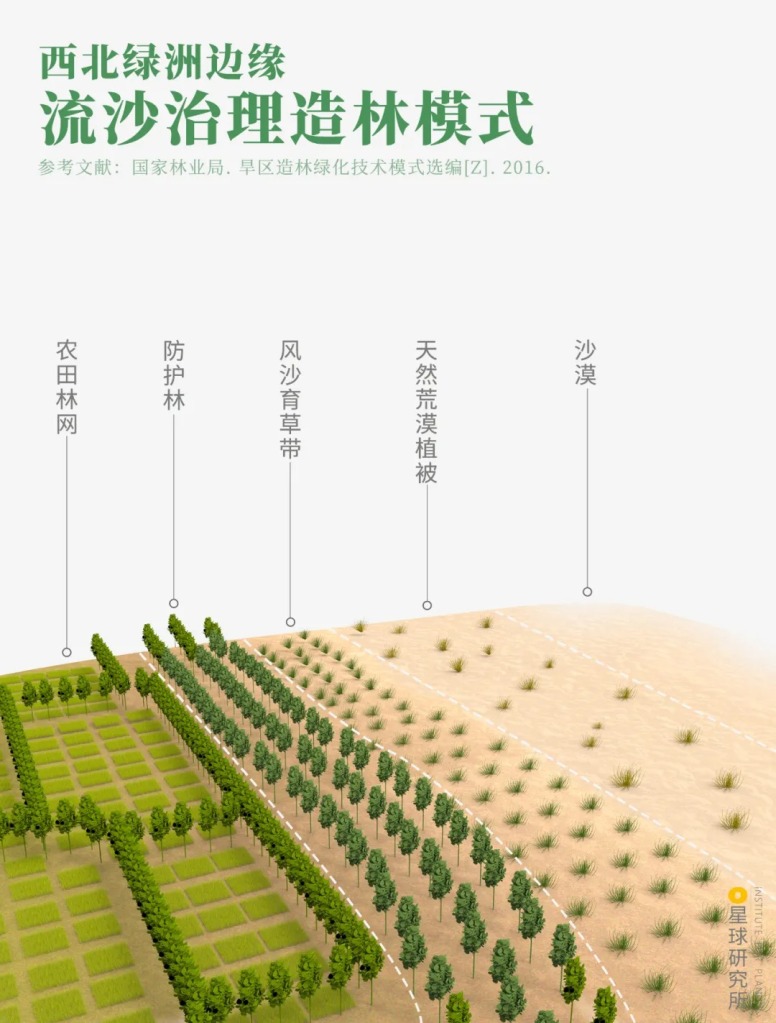

As arbors, shrubs and grass join forces, they form a comprehensive system with shelter forests being the core unit. Grass and shrubs form the first line of defence at the outermost zone, which is backed by the second defence line composed of shrubs and arbors. The core of an oasis is further safeguarded by a forest network. These three nested defence lines act as the guardian for farmlands, pastures, highways, villages and towns.

Left to right: farmland forest network (农田林网), shelter forest (防护林), sand barrier grass-nurturing belt (封沙育草带), natural desert vegetation (天然荒漠植被), desert (沙漠)

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

All kinds of windbreak and sand fixation forests have since sprung up everywhere in the arid and semi-arid zones in China, much like well-fenced green fortresses scattering across the barren land.

But the battle of wind and sand control does not just end here. The next frontline will be the juxtaposed regions along the 400-millimetre isohyet line, where shelter forests would be upgraded to an even large system.

3. The great green wall

The 400-millimetre isohyet line means much more than its name suggests. It insulates the arid zone and monsoon zone, separates forests and grasslands, defines the border for farming and nomadism, and draws the segregating line for population density.

Population density (人口密度), unit = person/sq km (人/平方公里)

(diagram: 巩向杰, Institute for Planets)

Farmlands and villages in the northeast, North China Plain and northwest are directly exposed to the Thousand-mile Sand and Storm Line. Hunshandake Sandland, situated to the north of North China Plain and just 180 kilometres from Beijing, is a giant sand source which continuously sends sand southward in the wind.

(photo: 陈剑峰)

To tackle this, a state-owned forest farm named Saihanba Mechanical Forest Farm was set up at the border between Chengde in Hebei and Inner Mongolia.

Saihanba used to be home to a vast sea of woods during the early Ming and late Qing dynasties. But when forestry experts arrived in 1961 to do a survey, it was nothing more than a dusty barren land. After days of inspection, they finally spotted one and only one larch tree in the entire Hongsongwa district residing in the northeast reaches of Saihanba.

(photo: 视觉中国)

This lonely larch might have been the solid proof of a degrading environment, yet it could also be seen as the hope to restore the ecosystem.

However, in order to plant trees here one had to first deal with the low temperature. The average annual temperature in Saihanba is only -1.2°C, and it can go down to -43.3°C during the coldest times.

(photo: 叶家骐)

Because of the cold, windy and dry climate, only less than 8% of all the imported saplings survived after planting. The key to solving this problem lies in autonomous nursery of seedlings, a process which begins already before sprouting so to ensure a high quality plantation. Whenever the bitter winters approached, these seedlings were taken to where they were supposed to be planted and buried below the snow, once the spring seasons returned they were planted swiftly on the spot to strive for a higher survival.

(photo: 王龙)

Workers also pioneered mechanical planting using tractors from Poland and tree planters provided by the Soviet Union, which greatly enhanced the efficiency of afforestation.

(photo: 王龙)

During the initial phase, tree planting was mainly done on relatively flat terrains. With technologies advancing by the day, workers began to set their eyes on rocky slopes. These slopes were not only steep and deep, but also lacked fertile soil. It took much more time and effort to do the same thing here.

(photo: 王龙)

Planting started with one slope at a time, but gradually workers managed to tame these stubborn rocky slopes of Saihanba in larger patches.

(photo: 王龙)

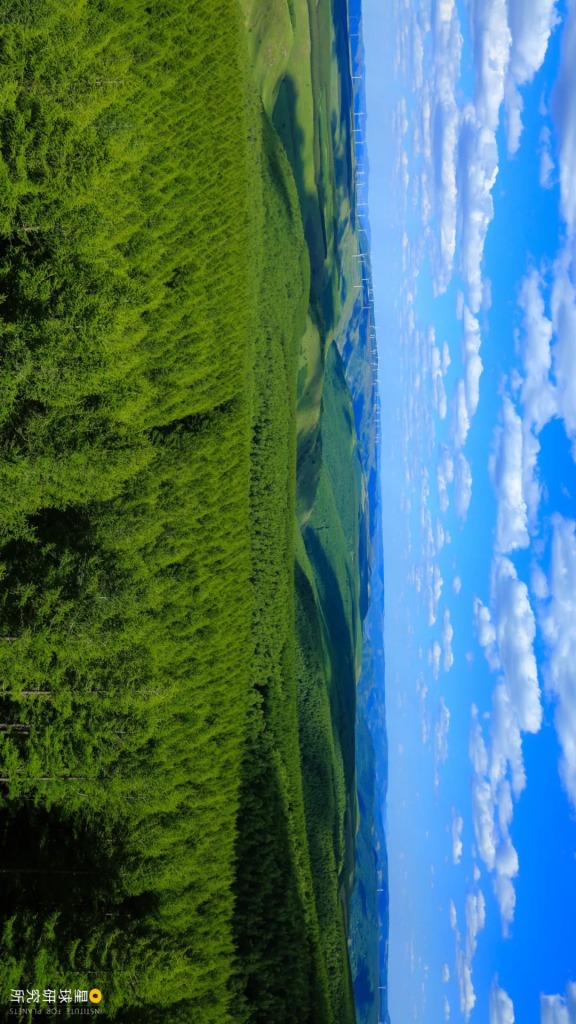

There are 1.12 million mou* of artificial forest in Saihanba today. Expansion of drifting sand is now effectively stopped by the dense woods, and the number of days with level 6 wind is substantially reduced.

* 1 mou = 0.165 acre, but may vary depending on the region

(photo: 王龙)

In addition to the forest farm, all kinds of shelter forests have risen around farmlands, villages, towns and cities. One of these is the farmland shelterbelt.

Belts of trees are planted perpendicular to the major wind direction, or along the roads and water channels. They also crisscross with each other around farms to build up a shelterbelt network against wind and sand.

(photo: 邓国晖)

These shelter networks lower wind speed and improve local temperature and humidity, thereby forming a microenvironment best suited for crop growth. The farmland shelterbelt network in the northeast, for instance, can increase the yield of corn by 10%.

(photo: 视觉中国)

Somewhat similar to farmland shelterbelt is the grassland shelterbelt. Some of these shelterbelts are planted in specialised arrays, much like the shape of Chinese words “田” and “目”, which are designed to protect pastures and livestocks. Those that are planted as grove islands are known as ‘green islands’ or ‘tree umbrellas’.

(photo: 王宁)

Shelterbelts are also built within villages and towns, cities, as well as industrial and mining areas to improve the local environment. This is done on top of street trees as well as community greening areas and parks.

(photo: 视觉中国)

All these shelterbelts are indispensable components of Taiheng Mountain Greening Project and Beijing-Tianjian Sandstorm Source Control Project, which aim to paint the Yan Mountains, Taiheng Mountains, Yin Mountains and Daqing Mountains green and improve the local ecosystems.

(photo: 邓国晖)

However, the challenges of economic development which China is currently facing is nothing less than that of the ecological preservation. The shortages in wood materials, fuels and feeds have frequently resulted in excessive deforestation. Therefore, shelterbelts should also possess an economic function that complements the ecological one. This is where economic-ecological engineering comes on stage.

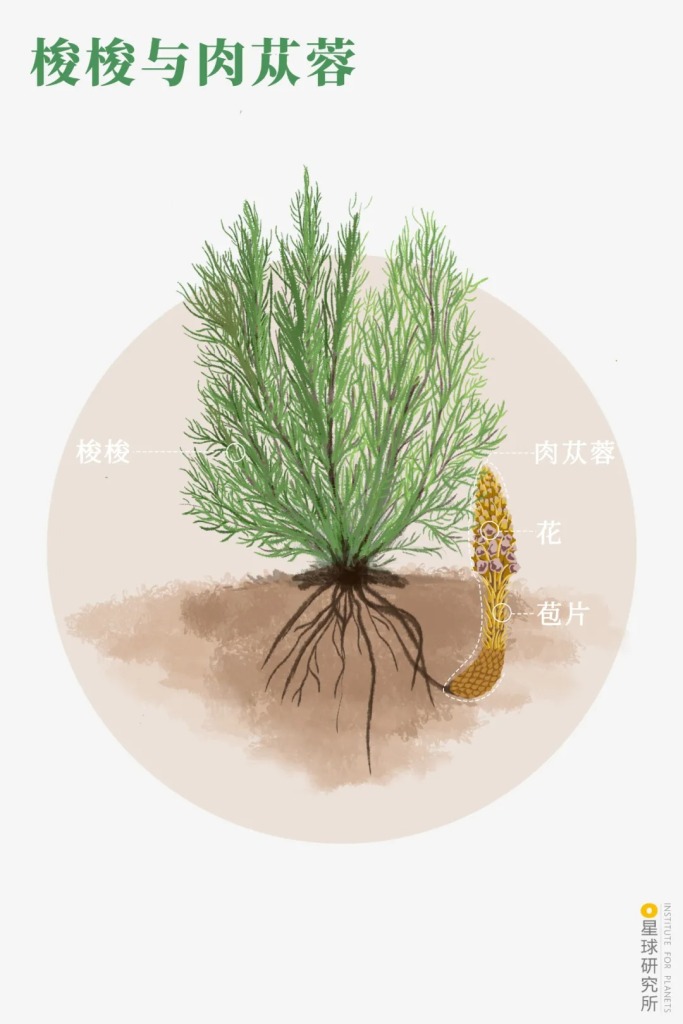

For instance, when saxaul forests in Badain Jaran Desert mature, cistanche can be planted to their root system. Commonly used as Chinese herbal medicine, this parasitic plant can bring about both economic and ecological benefits, and further ensures a promising outcome of the continuous development of shelterbelts.

Flower (花), bracts (苞片)

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

There are also specialised timber forests, firewood forests, and also economic forests that produce fruits, oils and medicinal herbs.

(photo: 视觉中国)

All these shelterbelts distributed across the northeast, North China Plain and northwest eventually merged into one comprehensive engineering programme in 1978, thereafter known as the Three-North Shelter Forest Programme.

From then on, the greening effort no longer comes from a single forest farm, but an entire system that covers an area of 4.06 million square kilometres spanning from Heilongjiang to Xinjiang. From snowy mountain peaks and glaciers to deserts and gobi lands, the programme covers all grasslands and farmlands alike be it at 100 metres or 5 kilometres above sea level. It also cultivates more than 3500 species of plants thriving in all sorts of climate and environment. It is without doubt a grand size mega project.

Major regions covered (left to right): Taklamakan Desert (塔克拉玛干沙漠), Gurbantünggüt Desert (古尔班通古特沙漠), Kumtag Desert (库木塔格沙漠), Qaidam Basin Desert (柴达木盆地沙漠), Badain Jaran Desert (巴丹吉林沙漠), Tengri Desert (腾格里沙漠), Xihaigu (西海固), Ulan Buh Desert (乌兰布和沙漠), Kubuqi Desert (库布齐沙漠), Mu Us Sandland (毛乌素沙地), Hunshansdake Sandland (浑善达克沙地), Hulunbuir Sandland (呼伦贝尔沙地), Saihanba (塞罕坝), Khorchin Sandland (科尔沁沙地)

(diagram: 巩向杰, Institute for Planets)

Between 1978 and 2017, the afforestation area of the Three-North Shelter Forest Programme totalled up to 460,000 square kilometres. Areas affected by soil erosion were reduced by 67% and the spreading of desertified land has been reversed. Compared to the year of 2000, the desertified area in 2017 was decreased by 18,000 square kilometres.

The sandland back then has now turned into an oasis

(photo: 魏蒙)

The Three-North Shelter Forest Programme is but a kickstart for the ecological engineering era in China. Many more ecological engineering projects are popping up everywhere in the country in hope to create even more green landscapes.

4. Rivers, lakes and the sea

So far we have been focusing mainly on the western and northern parts of China. Moving south and beyond the 400-millimetre isohyet, we will see a vast monsoon area with relatively abundant precipitation that is also facing its own unique predicament. There are many mountain ranges and rolling hills to the south of the isohyet, and such a terrain poses the first and foremost problem for afforestation. Before trees can even be planted, the steep slopes have to undergo large scale site preparation work known as slope engineering.

For slopes that are relatively gentle, levels of steps are excavated along the contour lines similar to how terraces are built. This process is called level-step site preparation.

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

Whereas for steep slopes, the steps have to tilt inwards so that the slope runoffs are guided towards the plant roots as much as possible. We call this reverse-slope terrace site preparation.

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

Another way is to excavate semicircular tree pits on the slope surface that are arranged in a “品” pattern. Owing to its unique appearance, this process is known as fish-scale pit site preparation.

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

Large scale site preparation has been instrumental in building numerous flights of green stairs, from mountain ranges in the north…

It took six decades for forestry workers to dress up the mountains in vivid colours

(photo: 视觉中国)

…to the southern rolling hills…

(photo: 视觉中国)

…as well as reservoir districts and river banks.

(photo: 胡寒)

The most representative of all are the soil and water conservation forests that populate the up- and midstream of various rivers. Vegetation coverage had risen rapidly on the Loess Plateau, from 32% in 1999 to 59% in 2013. The most prominent increase was seen in the Yan’an Prefecture, reaching 81% in 2017.

All these were accompanied by significant reduction in water and soil erosion. Annual sediment transport in the Yellow River has dropped from 1.3 billion tonnes in 1970s to not more than 300 million tonnes today.

(photo: 射虎)

According to the results of 2nd and 3rd Rocky Desertification Monitoring, the area of rocky desertification in karst areas went down by 16% between 2011 and 2016. Guizhou, the province with largest rocky desert area in China, scored the best performance with an 18.3% reduction.

(photo: 卢文)

Located at the headwaters of rivers are the water source conservation forests. They can be found encircling the major runoff areas of Yellow River, including the Qilian, Yin and Qinling Mountains, as well as far up in the northeast along the Khingan Mountains Ranges and Changbai Mountain.

(photo: 郑斐元)

The largest of these forests are those lining the upstream and midstream sections of the Yangtze River, including Jinsha, Yalong, Min, Han, Jialing and Wu Rivers.

(photo: 杜鹏飞)

The soil and water conservation forests and water source conservation forests cover a significant portion of the Yangtze River. Together they compose another enormous forestry engineering project known as the Upper and Middle Reaches of Yangtze River Shelter Forest Programme.

In the north is the Three-North Shelter Forest Programme (三北防护林体系工程)

(diagram: 巩向杰, Institute for Planets)

Similar shelter forest programmes are now gradually being implemented in Pearl River, Huai River, Tai Lake and Liao River.

But as we go further south and closer to the sea, new issues pop up. Unlike the inland, the coast is susceptible to damages from storm surges, in addition to wind and sand hazards in sandy areas and erosion problems originating from the coastal mountains. This is where coastal shelter forests come in handy, and one classic example of them is the mangrove forests in the southern coast.

Mangrove is not a tree of any specific species, but a generic term for the range of vegetations that are able to withstand coastal salinisation and charging sea waves. The artificial mangrove forest in the southeast coast has become a barrier that effectively weakens the land erosion by wind and waves.

(photo: 卢文)

All these ecological programmes cast a giant protection net coloured in green over the large rivers, lakes and the coastline in China.

Upper (left to right): Three-North Shelter Forest Programme (三北防护林体系工程), Middle Reaches of Yellow River Shelter Forest Programme (黄河中游防护林体系工程), Taihang Mountain Greening Project (太行山绿化工程), Liao River Basin Shelter Forest Programme (辽河流域防护林体系工程)

Lower (left to right): Upper and Middle Reaches of Yangtzei River Shelter Forest Programme (长江中上游防护林体系工程), Pearl River Basin Shelter Forest Programme (珠江流域防护林体系工程), Coastal Shelter Forest Programme (沿海防护林体系工程), Huai River-Tai Lake Basin Shelter Forest Programme (淮河太湖流域防护林体系工程)

(diagram: 巩向杰, Institute for Planets)

But as mentioned before, none of these ecological projects are perfect. In fact, they are facing a lot of problems in all aspects. How can we learn from mistakes in the past and lead a brighter future?

5. The past and the future

Controversies have never died down ever since the commencement of the Three-North Shelter Forest Programme in 1978. The upfront criticism points to the inappropriate afforestation in regions unfit for trees.

Much of the land to the west of the 400-millimetre isohyet is in fact not suitable for growing arbors, which were nevertheless planted in large quantities across the northwest in order to achieve wind breaking and sand control as swiftly as possible. While arbors grow quickly, they consume huge amounts of water. This overconsumption by arbors led to a drop in underground water level, which in turn cut off the water supply to themselves and devastated the forests.

(photo: 视觉中国)

Moreover, artificial forests in the early days often lacked sustained care after the initial plantation, or were composed of only a single planted species. All these problems resulted in low rate of forest preservation.

(photo: 丛日春)

But thanks to these experience, we are constantly improving such that our greening projects are supported by more rigorous science and the quality of afforestation is on the rise. For instance, we are now more focused on the biodiversity, which can be achieved through mixed planting of arbors, shrubs and grass, or combinations of tree species and a mixture of forest types.

In addition to afforestation, increasing attention is diverted to ecological restoration through programmes such as Natural Forest Protection Project, Returning Farmland to Forest Project and Returning Livestock Pastures to Natural Grasslands Project. These programmes relocate people who are stuck in inhabitable places of degrading land and scarce water source to areas with more fertile soil and relatively sufficient water supply. The idea of this ecological migration is to give the land a moment of respite to slowly restore the native ecosystem.

(photo: 视觉中国)

Running in parallel is the establishment of nature reserves, forest parks, all sorts of nature parks and the more integrated national parks.

(photo: 孙华金)

From grass grids in the northwest deserts to the green blanket covering much of the Chinese territory, we have come a long long way in the past 71 years and are finally seeing some results.

But admittedly, China is still one of the less green countries in the world. The forest coverage rate is still lower than the global average of 30.7%, and the per capita forest area is less than a third of the world’s average. The per capita forest stock is even lower at around a sixth of that around the world. And there are still vast stretches of drifting sand waiting to be dealt with.

In the 14th Five-Year Plan released recently, ecological engineering in China will be further upgraded. For this the entire Chinese territory will be divided into Three Zones and Four Belts (三区四带). Ecological compensation projects similar to Returning Farmland to Forest Project and Returning Livestock Pastures to Natural Grasslands Project will now replace afforestation and emerge to the foreground of the grand scheme.

Upper (left to right): Silk Road Ecological Shelter Belt (丝绸之路生态防护带), North Sand Belt (北方防沙带), Collaboration of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei (Jing-Jin-Ji) Ecological Governance (京津冀生态协同圈), Northeast Ecological Conservation Zone (东北生态保育区)

Lower (left to right): Qinghai-Tibetan Ecological Barrier Zone (青藏生态屏障区), Loess Plateau-Sichuan-Yunnan Ecological Restoration Belt (黄土高原–川滇生态修复带), Yangtze River Ecological Conservation Belt (长江生态涵养带), South Operative Restoration Zone (南方经营修复区), Coastal Protection and Disaster Mitigation Belt (沿海防护减灾带)

(diagram: 巩向杰, Institute for Planets)

On the other hand, tools for afforestation are no longer limited to shovel, pickaxes and digging machines. New game players include big data, 5G facilities, drones, artificial intelligence and aerospace technologies. One thing for sure is that by the time we step into 2035, we will be embracing a much greener future.

(photo: 视觉中国)

Last but not least, we would like to pay our most sincere respect to the countless individuals who have quietly made each and every one of these grandiose ecological projects possible.

They could be an ordinary couple who have tirelessly nurtured a forest farm for decades.

(photo: 视觉中国)

Or a three-generation family who have dedicated their entire lineage to sand control.

Photo was taken on 7 August 2019 in Babusha Forest Farm, Gulang County, Wuwei, Gansu

(photo: 视觉中国)

They could be migrants actively coming out from the mountains to help, or herders who offer to leave behind their pastures; they could be urban citizens who plant trees online via the Ant Forest, or forestry workers who actually carry tree seedlings up the hills. Every single and smallest act of theirs counted in the grand greening process of China.

(photo: 视觉中国)

(photo: 视觉中国)

(photo: 视觉中国)

And finally, we want to express our gratitude to every grass, shrub and tree that has been planted. To the projects, they may only be some insignificant ‘building parts’, but to those who planted them by hand, they are precious life and not so different from ourselves. They have always gone side by side and hand in hand with mankind, and it is our genuine wish that they will continue to be with us in the future as we stride forward.

Liquidambar does not catch fire easily and hence serves the purpose of a barrier

(photo: 视觉中国)

Production Team

Text: 成冰纪

Photos: 李嘉欣、余宽

Design: 罗梓涵

Maps: 巩向杰

Review: 王朝阳、云舞空城

Expert review (in alphabetical order)

Liu Bingru (刘秉儒), Researcher at Northern Nationalities University / Ningxia University

Lu Qi (卢琦), Researcher at Institute of Desertification, Chinese Academy of Forestry

Zhu Jiaojun (朱教君), Researcher at Shenyang Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

References

[1] 王治国 等. 林业生态工程学[M]. 中国林业出版社, 2000.

[2] 中华人民共和国生态环境部. 2019中国生态环境状况公报[R]. 2019.

[3] 国家林业局. 中国荒漠化和沙化简况[R]. 2015.

[4] 国家林业和草原局. 中国森林资源概况[R]. 2019.

[5] 国家林业局. 旱区造林绿化技术指南[Z]. 2016.

[6] 国家林业局. 旱区造林绿化技术模式选编[Z]. 2016.

[7] 朱教君,郑晓. 关于三北防护林体系建设的思考与展望——基于40年建设综合评估结果[J]. 生态学杂志. 2019.

[8] 颜长珍, 王建华 .中国1:10万沙漠(沙地)分布数据集,国家冰川冻土沙漠科学数据中心

… The End …