Focused on the People’s Republic of China (PRC), this article looks at how climate change impacts coastal ecosystems and marine biodiversity. In an era of global connectivity and shared environmental challenges, the linkages between oceans and climate change are becoming increasingly apparent. Oceans have the great potential to exacerbate or mitigate climate change and its related impacts, depending on the policies in place.

This extract analyzes the effects of sea-level rise and ocean acidification, considers how fisheries and vulnerable coastal ecosystems are affected.

INTRODUCTION

The world’s oceans—covering over 70% of the Earth’s surface—and climate change are directly and indirectly linked. For instance, the ocean plays a large role in global climate regulation via its system of currents, which distributes heat and moisture worldwide. Accordingly, ocean currents can greatly influence meteorological weather patterns such as precipitation and tropical storms. Ocean currents also transport nutrients and plankton worldwide, which are essential for healthy oceanic ecosystems.

The world’s oceans can absorb and store a vast amount of heat and carbon dioxide from the sun, natural processes, and anthropogenic activity. The world’s oceans are estimated to absorb approximately 90% of anthropogenic heat and 30% of anthropogenic carbon emissions. Without the presence of the oceans and their roles as carbon and heat sinks, the impacts of a warming climate would be even more severe. It is therefore vital to implement effective policies to protect and maintain the health of the oceans for climate change mitigation.

Studying the Relationship between Oceans and Climate Change:

the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special Report.

In 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. The report explains how different projected changes will impact communities and emphasizes the interconnections between society, the economy, the environment, and present and emerging risks.

The main findings of the IPCC report include the following:

(i) A multitude of documented changes in the physical compositions of the Earth’s oceans and cryosphere can be associated with anthropogenic climate change. For example, global ocean temperatures have risen since 1970 (virtually certain), and the rate of ocean warming has doubled since 1993 (likely).

(ii) Changes in the ocean and cryosphere and their associated risks are predicted to be far greater by the end of the century (2081–2100) if high greenhouse gas projections are followed, as opposed to low emission scenarios (very high confidence). The magnitude of change is calculated to be closely linked to the trajectory of greenhouse gas emissions, highlighting the need to act urgently and efficiently.

(iii) Both oceans and the cryosphere have demonstrated that they have ecological tipping points and that some changes may be irreversible (high confidence).

(iv) Communities in polar, mountain, and coastal environments are particularly vulnerable to ocean and cryosphere changes. Poor and marginalized groups in these communities are especially vulnerable to hazards and environmental changes (very high confidence).

(v) Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals remains challenging unless climate change-related issues impacting the oceans and cryosphere are addressed, especially

Sustainable Development Goals 13: Life Under Water.

THE IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON OCEANS OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA

Sea Temperature Rise

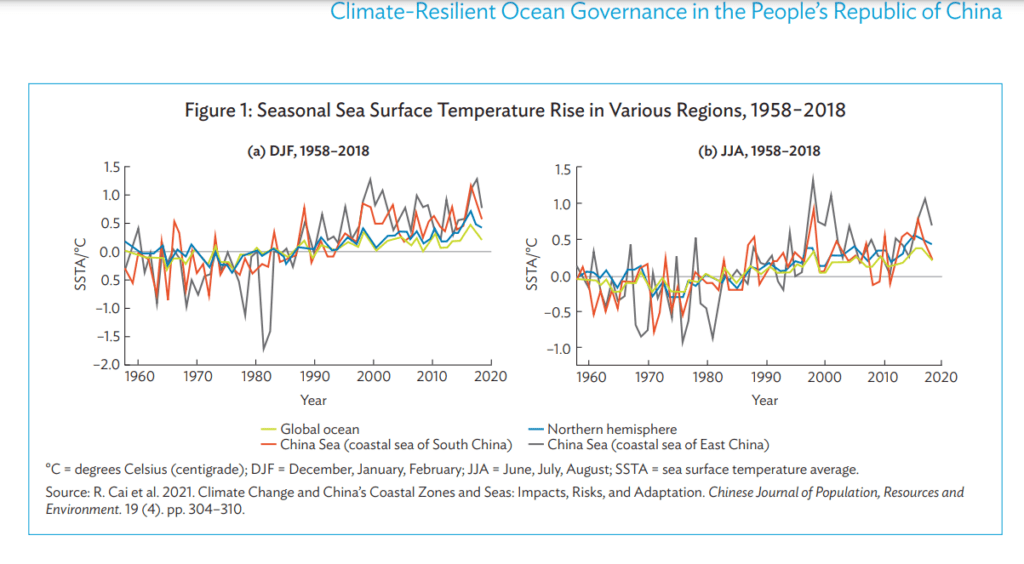

The ocean’s role as a heat sink and the increasing global temperatures have led to rising global ocean temperatures. Since the late 1970s, sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in China have increased at a higher rate than the global average. The SST of the PRC’s coastal and offshore waters is predicted to rise significantly during the 21st century and at a rate higher than the global average. Ocean warming may accelerate in the PRC for several reasons, including geographic location (influenced by factors such as solar radiation and ocean currents), land use changes, and water pollution. SSTs are also rising at varying rates across the PRC’s oceans, particularly the coastal sea of East China. This is due to many interconnecting factors such as ocean currents, monsoon patterns, levels of urbanization, and land–sea interactions. Even in different representative concentration pathway (RCP) scenarios, SSTs are predicted to rise at uneven rates (Figure 1).

Rising SSTs can significantly impact marine processes and ecosystems by triggering coral bleaching, changes in migratory patterns, disruptions to marine food webs, coastal ecosystem degradation, and heightened coastal vulnerability. Additionally, warmer waters can influence atmospheric temperatures and contribute to the formation of tropical storms and typhoons.

Sea Level

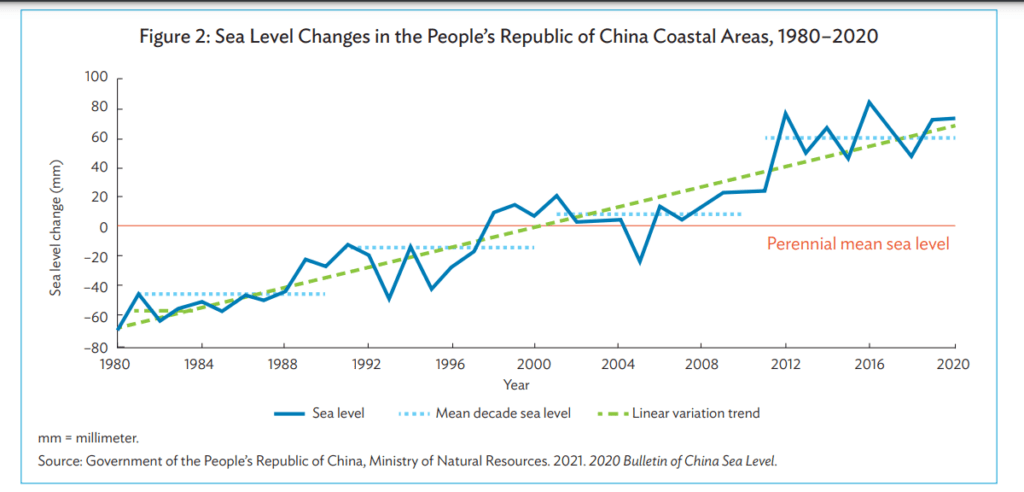

The sea levels of the PRC’s coastlines are rising. From 1980 to 2020, the average sea level rise rate of the PRC’s coastal waters was 3.4 millimeters per year, exceeding the global average during the same period (Figure 2). This increasing trend is set to continue as the sea level of the PRC’s coastal waters is projected to rise by 55–170 millimeters over the next 30 years. Sea level rise differs by region in the PRC, influenced by factors like geological conditions (areas which are subsiding—such as the northern part of the PRC’s Bohai Sea coast—experience higher rates of sea level rise), variations in air pressure, proximity to glacial melt, and human activities.

The long-term cumulative effect of sea level rise in the PRC’s coastal waters will directly cause shoal loss, lowland flooding, and ecosystem destruction. It will also increase the likelihood of and

exacerbate the effects of storm surges, flooding, salt tides, coastal erosion, and saltwater intrusion.

Ocean Acidification

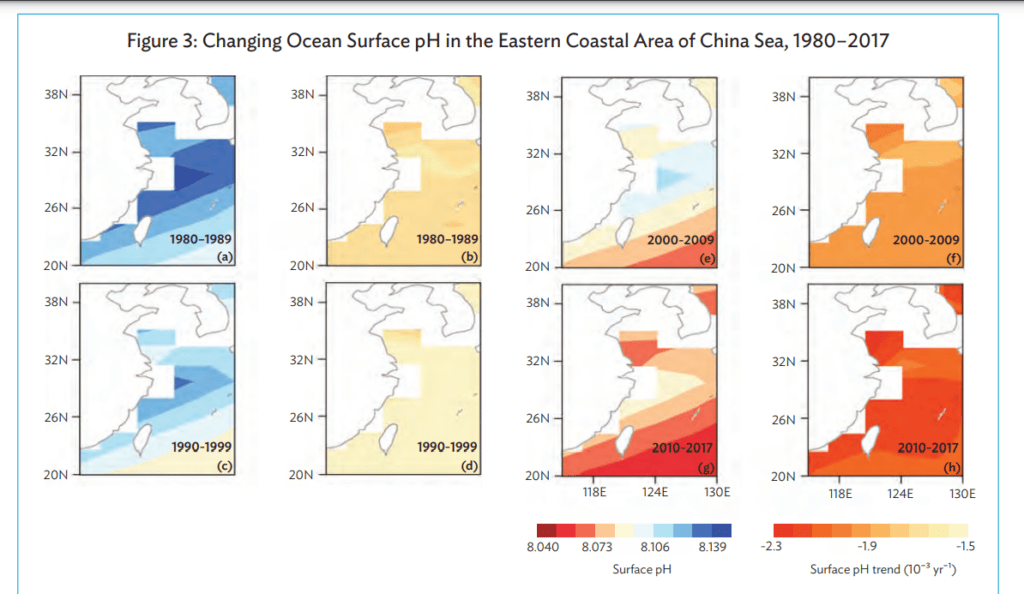

The ocean is a vast carbon sink that absorbs approximately onethird of anthropogenic carbon dioxide, contributing significantly to ocean acidification (pH), i.e., lowering pH levels in ocean waters. Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the pH of the

ocean’s surface has dropped from 8.21 to 8.10.

Increasing ocean acidification is documented in all of the PRC’s seas. For example, since 1999, the seawater pH values in the coastal sea of South China have significantly reduced, with an annual average decrease rate of about 0.012−0.014.10 Ocean acidification is particularly evident in the coastal sea of South China—compared to preindustrial times, the ocean’s surface pH declined from 8.20 to 8.06 in 2017, equivalent to a 35% increase in acidity (Figure 3).

Ocean acidification is highly detrimental to marine food webs by limiting the availability of calcium carbonate, which is necessary for the shell and skeleton formation of aquatic organisms such as foraminifera, sea urchins, sea snails, oysters, and corals. This has cascading consequences along the food chain and exacerbates pressures on biodiversity, ecosystems, and communities reliant on marine resources. Hence, ocean acidification is of particular concern in the PRC because of its economic dependence on fisheries.

Ocean Deoxygenation

Warmer water holds less oxygen as oxygen is less soluble in warm water than cooler water. This phenomenon—driven by ocean warming—is called ocean deoxygenation. Globally, oceanic oxygen content has decreased by more than 2% since the 1970s. Varying degrees of ocean deoxygenation have been observed in the PRC’s waters. For instance, from 1978 to 2006, the oxygenation of surface seawater in the central section of the Bohai Sea decreased at a rate of approximately 0.2 micromoles per kilogram per year, while in the deep seawater, the decline was steeper at about 0.8 micromoles per kilogram per year.

This substantial reduction in oxygen levels significantly impacts marine environments, altering the distribution, composition, and diversity of ecosystems and food chains. In extreme scenarios, ocean deoxygenation can cause “dead zones,” where oxygen levels are so low that the areas become partially or entirely uninhabitable for wildlife.

Marine and Coastal Ecosystems

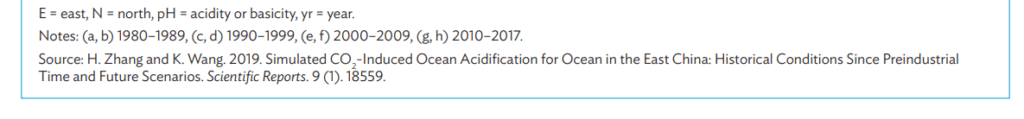

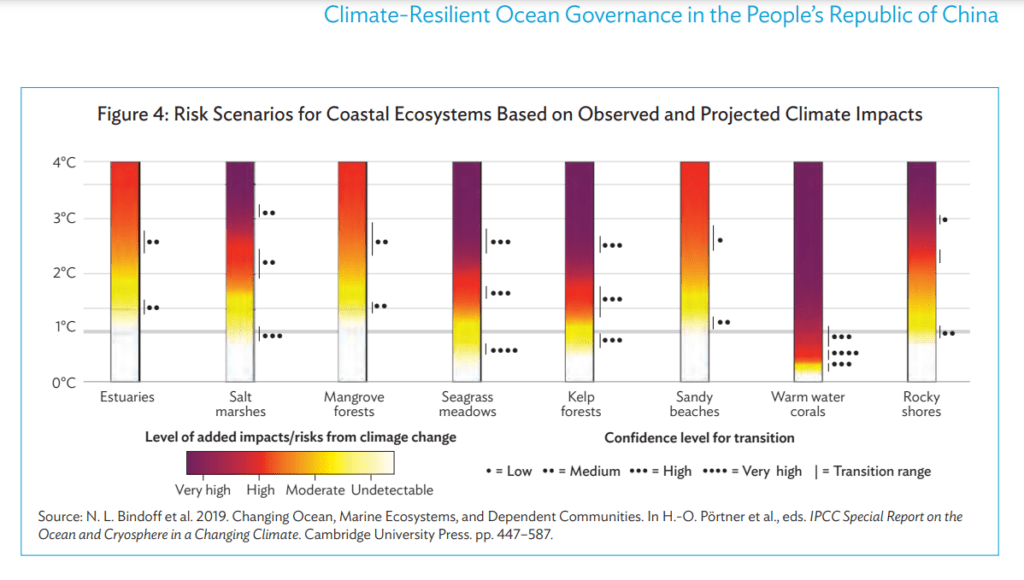

Coastal ecosystems worldwide are increasingly vulnerable to climate change, with the level of risk varying according to emission scenarios. High-emission pathways (e.g., RCP 8.5) exacerbate challenges, and low-emission pathways (e.g., RCP 2.6) offer some mitigation. Certain ecosystems are particularly vulnerable: coral reefs, kelp forests, seagrass meadows, and salt marshes (Figure 4). Estuaries are essential ecosystems as they act as the interface between freshwater and oceans and are vital for nutrient cycling. They are also essential to the PRC’s fishing industry and food security, as many commercially valuable fish species use estuaries for spawning and nursery areas. However, estuaries are at risk from rising sea levels, harmful algal blooms, deoxygenation, and anthropogenic pollution.

Salt marshes—intertidal zones flooded by seawater—offer multiple services such as carbon ioxide absorption, storm surge protection, water decontamination, and habitat provision. However, climate-related events like heat waves impact salt marsh fauna, and rising temperatures may introduce invasive species. Sea level rise intensifies rates of submersion, altering sediment features and salinity and potentially reducing carbon sequestration capacity. Mangroves are biologically diverse ecosystems that are highly effective in purifying water and protecting coastlines. However, they are vulnerable to rising temperatures (which hinder their growth) and rising sea levels (which could outpace adaptation).

From 1988 to 2020, the total area of mangroves decreased in the PRC from 1,559.34 hectares to 737.37 hectares because of unsustainable anthropogenic activity and climate change. Mangrove restoration is an increasing priority in the PRC, and mangrove restoration areas are slowly growing.

Seagrass ecosystems provide essential habitats, high productivity, water purification, and carbon sequestration. There are 22 recorded species of seagrass in the PRC, representing 30% of global species. However, sea level rise threatens seagrass beds through coastal erosion and direct submersion, impacting their physiology and distribution and ultimately reducing bed areas. The PRC has the world’s largest kelp cultivation industry, which is highly important for the country’s livelihoods and economic development. However, kelp forests are threatened by rising temperatures, shifting ocean currents, increasing acidification, and pollution. Furthermore, climate change impacts growth rates and enhances the proliferation of sea urchins—kelp’s natural predators—leading to overgrazing.

Coral reef ecosystems are highly vulnerable to climate change as they are extremely sensitive and have relatively narrow temperature requirements. Rising sea temperatures have triggered coral bleaching events, and ocean acidification further undermines the formation of their coral skeletons. The PRC’s coral reef systems are generally degrading, indicating the declining ocean health in the country’s seas and globally

Fisheries

The PRC is the largest contributor to global fisheries production. However, the country’s fisheries sector is experiencing severe declines in biomass and biodiversity due to unsustainable human activity and climate change. Since the 1960s, ocean warming and unsustainable fishing techniques have depleted fishery resources in the PRC’s offshore waters. This resulted in reduced numbers of biologically important species, community diversity, trophic levels, fish sizes, shorter life spans, and earlier sexual maturity in certain species. Some traditionally economic species—such as little yellow croaker, hairtail, and butterfish—no longer have fishing seasons because of climate change and overfishing. Wild capture fisheries in the PRC are also facing similar challenges.

Climate change is also shifting the distribution of fish in the PRC. Marine fish are predicted to deviate from their conventional habitats by more than 40 kilometers every decade. For instance, during 2010–2019, approximately 25% of the habitats of 20% of fishing species in the Chinese seas became uninhabitable because of ocean warming. Estimates suggest that nearly 50% of species will not be able to live in 25% of their current habitats by 2050. Under RCP 8.5, there will be severe declines in commercial fish species, putting regional fishing economies at risk of collapse.

Disaster Risk Management

Climate change has amplified coastal and oceanic hazards across the PRC.30 This is especially important when considering that coastal cities in the PRC account for 20% of the total population. For example, the northwest Pacific coast — where the PRC is located — suffers from the world’s most frequent, intense, and widespread tropical cyclones. Accordingly, the PRC is among the nations most impacted by these hazards. On average, the country used to experience seven typhoons per year, with annual losses of roughly $5.6 billion. However, the increasing frequency and intensity of these hazards puts lives, ecosystems, and infrastructure at risk. For instance, in July 2023, the PRC faced several extreme weather events, including two typhoons. The economic losses from hazards during that month alone reached $10.5 billion, greater than those ecorded in the first 6 months of the year. Agriculture was particularly impacted because of crop damage and livestock losses.

Source: Asian Development Bank (ADB), August 2024. http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/BRF240388-2

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO)

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors (Dongmei Guo, Christian Fischer) and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of ADB or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included here and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use.

Asian Development Bank

Metro Manila, Philippines