Key BRICS country Russia has the resources to become a world leader in alternative energy.

Russia is vast country that possesses huge renewable resource potential, including hydropower, solar and wind, green hydrogen and huge swathes of forest and arable land for bioenergy. It has the level of technological development required to foster an energy transition towards renewable resources, yet it lags behind other world powers in its deployment of renewables.

Russia also has ample oil and gas reserves to both supply energy to all its people and earn huge revenues from exporting fossil fuels. Oil, gas and coal account for more than half the central government’s revenue, and the associated industries are responsible for 20% of the country’s GDP – Russia is the fourth biggest national emitter of greenhouse gases in the world. Russia possesses the world’s largest natural gas resource, the second largest reserves of thermal coal, and arguably the sixth largest oil reserves, which helps explain its lack of interest in renewables.

History of Alternative Energy in Russia

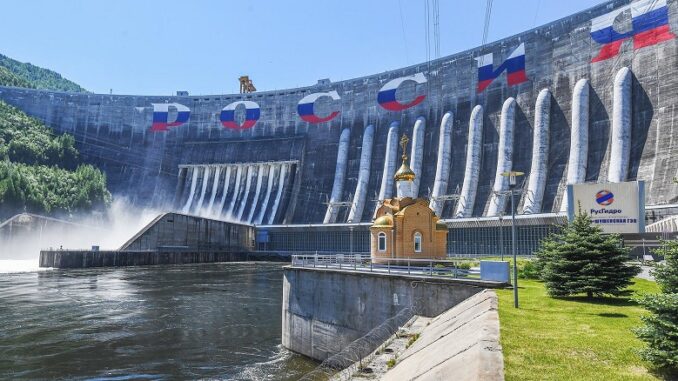

Hydropower

Despite the emphasis on fossil fuels, Russia has been actively harnessing non-fossil fuel energy sources for many years. Hydroelectric projects began in the 1930s and a number of large dams were built in the ‘50s and ‘60s, although many fell into disrepair in the post-Soviet era recession. The country currently has about 100 hydroelectric plants with a capacity of over 100 MW, and ranks fifth in the world for hydropower production. Around 20% of Russian power is sourced from hydropower but it has been estimated that only a fifth of Russia’s hydropower resource, potentially up to 852 TWh, has been accessed, although much of this yet-to-be exploited potential is found in areas far from major user centres.

Geothermal Energy

Geothermal energy has also been tapped in Russia for over 60 years. The first geothermal station was built in 1966 in Kamchatka, where the power is used for heating buildings, whilst in other areas geothermal energy is used directly, in cattle and fish farming, drying agricultural products, and heating greenhouses and swimming pools. Many regions have potential for this resource, with hot geothermal liquid accessible in the northern Caucasus, the Baikal Rift area and Western Siberia, as well as Kamchatka, where thermal water reaches temperatures in excess of 300°C.

Nuclear Power

Another non-fossil fuel energy source, nuclear power, has long been important in the Russian energy mix. Possessing plentiful uranium resources, Russia actually built the world’s first nuclear power plant, a 5 MW reactor, in Obninsk, about 100 km south-west of Moscow, which was connected to the grid in 1954. Currently, the country operates 38 nuclear power reactors and sees the role of nuclear, which at present accounts for about 20% of Russian power, increasing in the future, with research concentrated on the development of new reactor technologies and also in building floating nuclear power plants, primarily in the Arctic.

Wind and Solar Potential

Russia’s first windmill for generating electricity was built in 1941, but progress in this sector has been slow, although the production of electricity from wind has increased by 30% since 2000 – reportedly nearly 70% in 2018 alone. There is huge potential for development in this area; it has been estimated that wind power could produce as much as 17,000 TWh and it could account for 11% of total energy capacity by 2030. Much of Russia is ideal for the development of wind farms, especially the North-western, Southern, Siberian, Ural, and Far Eastern Federal Districts, where there are large amounts of unoccupied land. In the more remote areas, which tend to rely on old diesel power stations, it would seem an obvious solution. The slow pace of wind energy development is partially due to the harsh climate, as well as logistical issues and technical problems, like a lack of proven solutions for integrating wind generators with diesel power stations.

Figure 1 – Mean wind speed map for Russian Federation showing wind power potential.

Solar power has been particularly slow to develop. The first plant opened in 2010 but installed capacity has since increased quite rapidly to about 1.3 GWh by 2019. A number of projects are now under construction, with the tariff system encouraging several recent joint ventures, including a 45 MW solar power plant that opened in March 2021 in the Buryatia region, close to the Mongolian border, which boasts 300 sunny days a year. It has been estimated that the country has a gross solar energy potential of over two million tonnes of coal equivalent, with the Black and Caspian Sea regions, North Caucasus, Far East and Southern Siberia being the areas where solar energy could be most readily accessed. It is suggested that even Russia’s many Arctic settlements could benefit from hybrid solar-diesel power stations that would cut costs and minimize supply chain and shortage problems.

Further Green Potential

With its vast uninhabited land area, including about 20% of global forests, and large quantities of agricultural waste, Russia is thought to possess the world’s largest biomass resources. It is one of the biggest producers of wood pellets and the industry is expanding fast, although it should be remembered that the forests are an important carbon sink. It is thought that the country currently only makes use of 12% of its bioenergy potential.

Figure 2 – Renewable energy potential in Russia.

Tidal power also has potential. One of the world’s largest tidal power plants, Kislaya Guba in the Barents Sea, with a total capacity of 1.7 MW, was built in 1968 and there are plans to develop a huge 87 GW project at Penzhin Bay in the sea of Okhotsk, which has an average tidal height of 10m.

Limited attention has been given by the government to the development of the technologies required for alternative energy solutions, making their costs higher than elsewhere; the insistence on local content technology does not help. The harsh environmental conditions in the country are another factor, especially the long, hard winter. Ice has a particularly detrimental effect on wind turbines, while snow covering a solar panel stops it working and freeze-thaw effects can cause major problems, all making maintenance more expensive.

Energy transition in Russia would be expensive; a top Kremlin aide said before the COP26 summit that it could cost Russia’s economy roughly $1.2 trillion by 2050. To achieve the goal of cutting greenhouse gas emissions by 79% by 2050, Russia would need to invest about $45 billion per year into alternatives to fossil fuels.

Source: GeoExPro, August 19, 2021. Extracts from ‘A Carbon-Free Russia: Barriers and Opportunities’. https://geoexpro.com/a-carbon-free-russia-barriers-and-opportunities/