Government report finds number of native fish and protected wildlife species up over previous year, but there is much room for improvement.

The Yangtze – China’s longest river and a critical habitat for aquatic life – is showing signs of ecological improvement, the latest government report says, while warning that there is still a long way to go to protect biodiversity in its waters, especially rare and endangered species.

In a communique released on August 12, 2024 the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs and two other ministries said a series of policy measures to protect the Yangtze River had resulted in improved habitats and environmental indicators.

The measures were centred around a 10-year fishing ban imposed in 2020, according to the document also signed by the Ministry of Water Resources and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment.

Aquatic biodiversity had steadily improved since the implementation of the ban, the statement said, with 227 species of native fish monitored in the Yangtze River basin last year, an increase of 34 species from the previous year.

Additionally, 14 species of nationally protected aquatic wildlife were recorded in 2023 – three more than in the previous year.

Their habitat conditions were also generally stable, the communique stated.

The overall water quality of the Yangtze and its tributaries had been rated as “excellent”, and the intensity of new development projects affecting fisheries, such as sand mining and waterway regulation, had decreased, it said.

Aquatic biological resources, including fish, invertebrates and amphibians, had continued to recover, with a 16.7 per cent increase in resource density – or the number of aquatic animals per unit area – in the main channel of the Yangtze, and more than 64 per cent increase in major tributaries compared to 2022.

However, the situation remains alarming, according to the communique.

The diversity of key protected aquatic wildlife species was still relatively low, it warned, adding that the preservation of endangered species remained a tough task.

In particular, the Chinese paddlefish and the Yangtze sturgeon, known as the “last giants of the Yangtze”, had lost their ability to breed naturally, the communique said.

The two wild freshwater species were declared extinct in 2022 by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, largely as a result of dam construction and overfishing.

Some sections of the river are also threatened by poor water connectivity and shoreline hardening caused by human activities such as sea wall installation, resulting in poor scores on measures of ecological health.

The Yangtze’s aquatic biological integrity index – a scoring system based on fish population indicators and other ecological factors – is categorised into six levels: excellent, good, fair, poor, very poor and “no fish”.

In 2023, the Yangtze and its two largest freshwater lakes, Poyang and Dongting, were rated as “poor” on the index, although this was an improvement from their “no fish” status before the fishing ban.

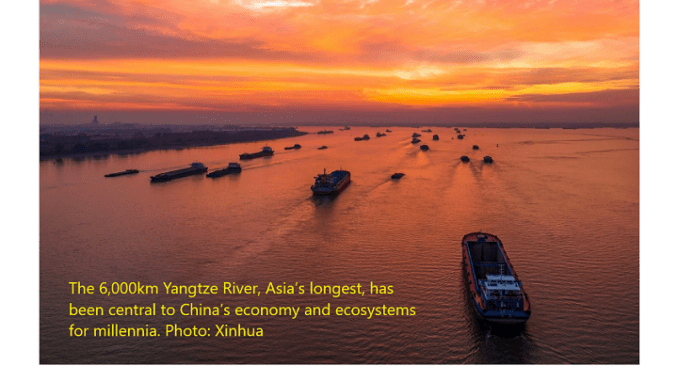

As Asia’s longest river, the 6,000km (3,728-mile) Yangtze has been central to China’s economy and ecosystems for millennia. Teeming with more than 400 fish species, 22 of which are listed as nationally protected, it has also long been the source of much of China’s aquatic biodiversity.

But decades of man-made damage, marked by hydropower development on the river’s main channel beginning in the 1970s, have had a devastating impact on the survival of species.

When President Xi Jinping inspected the upper reaches of the Yangtze in January 2016, he saw a river plagued by industrial waste, sand mining and boat emissions, with deteriorating water quality.

The mother river had fallen “ill, very ill”, Xi said, calling for all-out efforts to protect the Yangtze.

“Restoring its ecological environment will be an overwhelming task at present, and for a rather long period to come,” Xi said.

The same year, an environmental protection inspection group led by ministerial-level officials was set up to target activities that undermine the river’s ecology, including illegal sand mining.

The 10-year fishing ban ordered in 2020 covered more than 332 conservation sites along the river to help rehabilitate the ecosystem.

In December that year, Beijing passed the Yangtze River Protection Law to strengthen ecological protection and safety, and promote the efficient use of resources along the river basin.

The law, which took effect the following March, included the 10-year ban on commercial fishing on the Yangtze sites. This was extended the same year to cover the main river, and its major tributaries and lakes as well.

However, ecological departments are still being admonished for “not fully understanding the importance” of restoring the waterway’s environment.

According to a report issued in May by the Central Supervision Office of Ecological and Environmental Protection, the Yangtze and the Poyang and Dongting freshwater lakes are still being damaged by pollution and illegal activities.

The office, under the ministry of the same name, leads Communist Party and government officials of all levels to share accountability for ecological and environmental protection in addition to their work duties.

Source: South China Morning Post, 24 Aug 2024. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3274978/biodiversity-chinas-yangtze-river-improves-endangered-species-still-under-threat

Author: Dannie Peng in Beijing

Article republished under Creative Commons licence.