A 26.5 million-year-old skull found in northwest China has been identified as another extinct species of giant rhino, one of the largest mammals to ever roam the land.

The fossil is remarkably well-preserved, and after close analysis, scientists have named it Paraceratherium linxiaense, the sixth species of this hornless rhino genus to be uncovered in Eurasia.

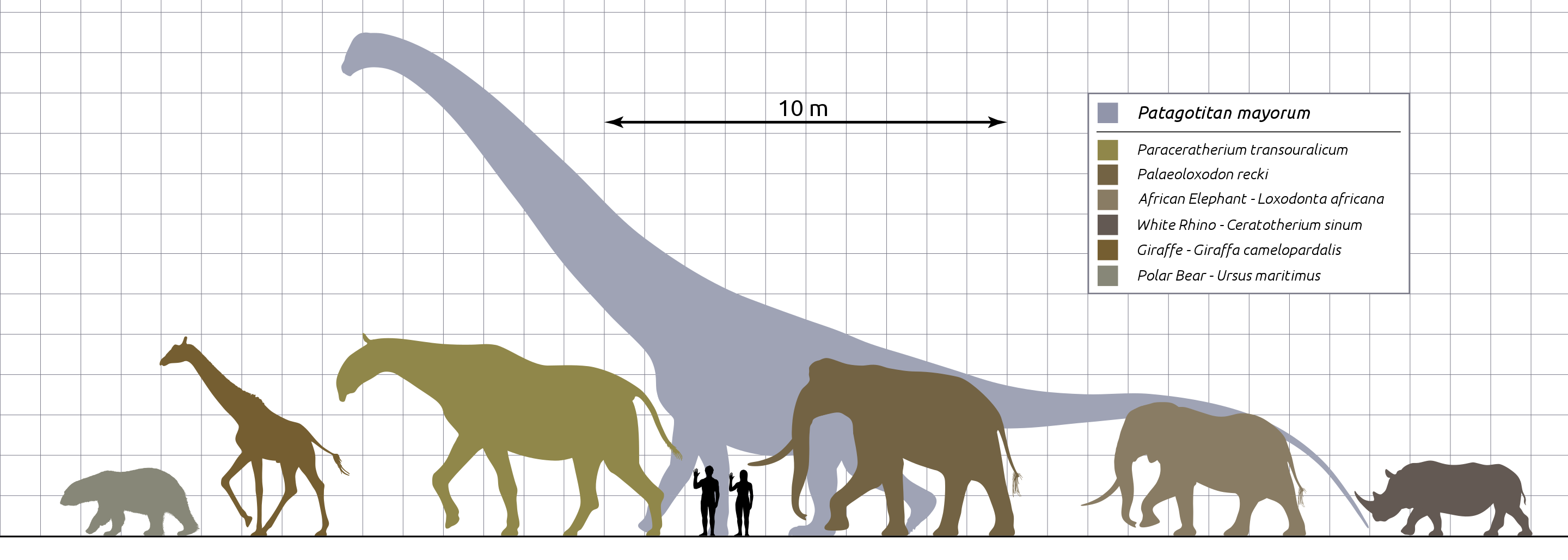

It’s hard to infer the exact size of the beast from its skull alone, but other Paraceratherium fossils suggest these creatures once stood on four surprisingly skinny legs at a shoulder height of about 4.8 meters (15.7 feet), which is roughly the size of the largest modern giraffes. Today, modern rhinos stand barely two meters tall (10 feet).

But it’s the beast’s mass that makes it stand out as a true land behemoth. While a lack of complete fossils makes it hard to pin down, estimates vary anywhere from 11 to 20 tonnes – roughly the same as three to five African elephants combined.

Judging from the skull of this big fella, researchers think P. linxiaense could be the largest giant rhino in its genus (although the team doesn’t give any objective dimensions).

The giant rhino skull of P. linxiaense compared to the technician. (Tao Deng)

The giant rhino skull of P. linxiaense compared to the technician. (Tao Deng)

Compared to other giant rhino fossils found, the newly discovered species has a relatively short nose trunk and a long neck, with a deeper nasal cavity.

Together, the features more closely resemble the giant rhino, P. lepidum, which has been found in Kazakhstan and other regions of northwest China. Another species found further south, called P. bugtiense, is smaller with a shallower nasal cavity.

The trail of fossils has scientists thinking giant rhinos once migrated from the Mongolian Plateau, into northwest China and Kazakhstan, and down into Pakistan, likely via Tibet.

At each location, the genus appears to have become highly specialized to its environment, leading to the branching of various species during the Oligocene between 34 and 23 million years ago.

The team’s phylogenetic analysis places P. linxiaense somewhere in the middle of this transition, right before giant rhinos made their way through Tibet.

During this time, it’s possible the Tibetan plateau might have hosted a mosaic of forests and open landscapes. In such an environment, giant rhinos would have had no problem finding the huge volume of leaves and scrub they likely had to eat to maintain their massive frames.

“These findings raise the possibility that the giant rhino could have passed through the Tibetan region before it became the elevated plateau it is today,” the team hypothesizes.

“From there, it may have reached the Indian-Pakistani subcontinent in the Oligocene epoch, where other giant rhino specimens have been found.”

(Wikimedia Commons/CC BY SA 4.0)

(Wikimedia Commons/CC BY SA 4.0)

Above: Estimated size of P. transouralicum (third from the left) compared with that of humans, other large mammals, and the dinosaur Patagotitan mayorum.

Today, rhinos are known for their horns (perhaps too much so), but it actually took a while for these prehistoric-looking appendages to evolve. Most rhino ancestors don’t have them. In fact, for the longest time, early rhinos resembled tapirs, which themselves look somewhat like wild hogs with stumpy trunks.

Paraceratheriums are a sub family of the super family Rhinocerotoidea, which modern rhinos belong to. For 11 million years, their giant shadows fell upon the Earth, from far north Mongolia to Pakistan. No one knows what happened to them at the end.

Source: Science Alert, 17 June 2021. The study was published in Communications Biology.