Is Bitcoin an example of the worst excesses of rampant neo-liberalism?

Patrick Li’s Bitcoin mine used to be filled with the persistent hum of rows and rows of computers, all busy around the clock solving the complicated mathematical puzzles needed to keep the world’s most popular cryptocurrency operational.

Li, 39, had set up shop in the northern Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, which once welcomed businesses like his to use the abundance of locally produced coal-powered electricity.

But last year, China’s central government admonished Inner Mongolia for missing its electricity consumption reduction targets. As a result, in March, the region decided to show certain energy-intensive industries the door, including cryptocurrency mines like Li’s.

“It was all of a sudden,” Li says. “We have no choice but to look for a new location.”

The policy reversal has China’s Bitcoin mining community wondering whether its time in the country is running out. Will other regions and provinces follow suit now that President Xi Jinping has made reaching carbon neutrality a major government goal? For now, Bitcoin’s fate is in limbo. Li Bo, vice president of China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China, told reporters in April that policymakers are currently deciding on what regulations to apply to the virtual currency.

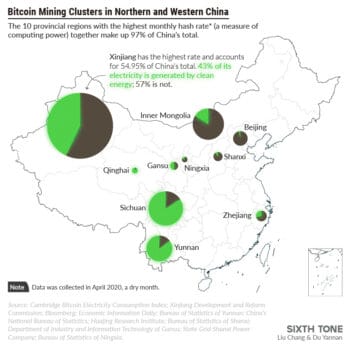

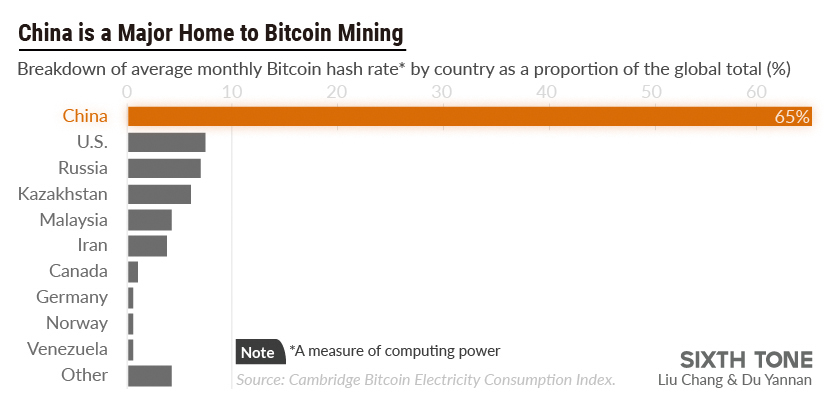

Any outcome will be felt globally. The country’s share of the entire Bitcoin network’s hash rate–a measure of computing power–stood at 65% in April 2020, the most recent available figure at the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (CBECI). The global Bitcoin community was reminded of China’s central role when, after a fatal coal mine accident in April, authorities in the northwestern Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region launched safety checks that disrupted power supplies to local Bitcoin mines, and hash rates fell by up to 30%.

Energy nomads

Like many other blockchain-based currencies, Bitcoin is decentralized, meaning there is no bank or country in control. Instead, miners use computing power to verify transactions, for which they receive bitcoins in return. In 2013, Li smelled a business opportunity. He decided life as a civil servant wasn’t for him, spent a month’s salary on a computer, and began mining Bitcoin, in pursuit, he says, of “financial freedom.”

Back then, he was far from the only one. Given China’s position as a manufacturing hub for electronics, the right equipment was easy to get hold of. Local governments were eager to attract what they saw as “high-tech” industries, and China grew to become the dominant cryptocurrency country it is today. Over the years, Li witnessed bull markets that minted millionaires, as well as collapses that crushed dreams. His only regret is selling Bitcoin he now knows he should have held onto.

Bitcoin is coded to create competition. Whichever miner does the quickest calculations for a particular set of transactions receives the reward. This has set off an arms race, with miners incentivized to use as much top-of-the-line equipment as possible, racking up enormous energy bills. Luckily for them, the price of Bitcoin has risen, too. At the start of 2013, the year Li began, 1 bitcoin was worth $13.40. With the exchange rate above $50,000 for much of 2021, mining remains exceedingly profitable.

But the environment bears the cost. An article published April in scientific journal Nature Communications concluded China’s Bitcoin-mining industry was on track to be responsible for 130 million tons of carbon emissions by 2024, exceeding the total greenhouse gas emissions of the Czech Republic.

The immense power needs of Bitcoin mining determine where profits can be made. “Like nomads looking for places with water and grass, we miners seek places with cheap and stable power supply,” says Liu Fei, CEO of Bixin Mining, one of China’s largest cryptocurrency companies. Chinese cryptocurrency miners alternate between areas rich in hydropower during the rainy summer, and return to northern areas like Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia that are rich in coal-fired electricity during the dry season. Some go to even greater lengths to cut costs. Last year, authorities discovered a Bitcoin mine disguised as burial tombs stealing electricity from a nearby company.

“The fact that whoever has cheap energy has more Bitcoin mining capacity shows that Bitcoin is essentially an energy currency,” says Xu Peng, a professor of mechanical engineering at Tongji University who specializes in sustainability.

An often proposed solution to Bitcoin’s energy footprint is replacing the current mining mechanism, called “proof of work,” with “proof of stake”–a way to verify transactions that doesn’t require nearly as much computing power. But its decentralized nature makes such fundamental changes difficult, says Xu. Bitcoin miners are unlikely to agree to something that would render their expensive hardware useless. Moreover, Bitcoin’s high valuation is a reflection of its mining costs, which include energy, says Liu: “Like gold, it is scarce because it is difficult and expensive to mine.”

Policy shifts

For a while, less developed regions eager for investment welcomed the cryptocurrency mines, allowing them to register as data centers and providing discounts on electricity and land fees. Until February, Inner Mongolia used an “inverted price ladder” for energy-intensive industries. The policy, which attracted many Bitcoin mines, lowered the price of electricity the more a business consumed.

But the winds have changed, and the Chinese government now wants to reduce energy use and related greenhouse gas emissions instead. According to 2020’s figures, 85% of Inner Mongolia’s electricity is generated from fossil fuels. In the city Ordos, where Li was located, that figure is 94%. With the central government looking to limit coal consumption, power-hungry Bitcoin mines are an obvious target, says Yang Zhou, China advisor at energy and climate policy think tank Agora Energiewende. “Because (Inner Mongolia) hadn’t adjusted how it supplied power, it could only cut off demand to meet emission-control targets,” she says.

Guan Dabo, professor at Tsinghua University and co-author of the paper calculating Bitcoin’s carbon footprint, told Sixth Tone that, to him, the drawbacks of cryptocurrencies outweigh their benefits to the country’s prosperity. “This emerging industry does not have much substantial contribution to the future national economy,” Guan says.

As a financial derivative tool, it consumes a lot of energy. It may not be worth the gain.

China’s policymakers seem to increasingly share Guan’s doubts. In April, the municipal government of Beijing told data centers involved in Bitcoin mining to report their electricity consumption to inform future policy, and announced it would tighten supervision and approval of data centers out of energy saving concerns. An official said the excessive growth of data centers had “put pressure” on the city’s ability to control carbon emissions and meet power demand during peak periods.

China’s central government has long been skeptical of cryptocurrencies. Already in 2013, the central bank banned financial institutions from using and trading in Bitcoin and similar currencies. In 2017, China shut down domestic cryptocurrency trading platforms and outlawed launches of new cryptocurrencies, called initial coin offerings. Chinese people can still trade via foreign exchanges, but at the risk of the policy climate becoming even stricter.

“Chinese policy does not recognize the currency properties of Bitcoin, worrying that it might impact currency management and the financial system,” says Huang Zhen, director of the Institute of Financial Law at Central University of Finance and Economics. “At present, the only virtual currency recognized by China is the digital yuan”–which is backed by the People’s Bank of China.

“What are the benefits of digital assets to the real economy? We’re approaching this issue with caution,” Zhou Xiaochuan, former president of the People’s Bank of China, said at an international conference in April. He compared cryptocurrencies to shadow banking and the speculative trading of derivatives that caused the 2008 financial crisis. “We need to be careful,” he said.

When it comes to cryptocurrency mining, the central government is more ambiguous, neither banning nor supporting such businesses. This lack of clear guidance means local regulations can be unpredictable. Many miners, for example, sign contracts with small-scale hydropower dams and coal-powered plants, both of which have been the subject of mass closure campaigns. As a result, Li says, miners focus on short-term profits, aware it might not be possible to bring long-term plans to fruition.

Li’s own experience is a case in point. Though he never expected Inner Mongolia to ban cryptocurrency mines outright, the move was preceded by an inspection round in 2019 targeting energy-intensive mines taking advantage of electricity discounts, and, in August, the suspension of 21 Bitcoin mines from taking part in electricity trading, meaning they could no longer enjoy preferential prices.

Where to next?

Bitcoin mine investors tell Sixth Tone they expect the policy changes in Inner Mongolia to sooner or later be copied by other regions rich in coal and cryptocurrency mines. Their chief concern is Xinjiang, which, according to CBECI, is home to a third of the world’s Bitcoin mining.

On Thursday, the central government gave Bitcoin miners a potential first sign of things to come. Xinjiang was among seven province-level areas it reprimanded for failing to control energy intensity during the first quarter of the year, urging them to “resolutely take down projects that don’t meet standards and that consume a lot of energy and cause a lot of emissions.” It was essentially the same warning given to Inner Mongolia last year.

Wu Jihan, a leading Bitcoin entrepreneur and co-founder of mining-chip giant Bitmain, reminded fellow miners during an industry conference in April that they had to start using clean energy or risk institutions losing interest in “dirty” Bitcoin. “Carbon neutrality has a long-term impact on the industry, and reducing carbon emissions is a global trend,” he said. The conference celebrated the upcoming wet season, a source of cheap electricity. “Hydropower,” Wu said, “is the heirloom of the mining industry”–something to be treasured for generations.

Many miners have placed their hopes–and computers–in two southwestern provinces rich in hydroelectric dams: Sichuan and Yunnan. Because of a lack of infrastructure to send electricity long distances, these dams often curtail their power–in Sichuan, the total stood at over 20 billion kWh for 2020, 5.7% of their total production and about twice the electricity used yearly by Washington D.C. This has historically attracted energy-intensive industries, from chemical and aluminium plants to cryptocurrency mines.

Many miners focus on Sichuan, owing to a provincial policy, in effect since 2020, to support the blockchain industry with over-capacity hydropower for three years. “Sichuan has the most friendly policy toward Bitcoin mining in China,” says Yang Maohua, who runs Bitcoin mining operations in the province.

But Sichuan’s Bitcoin mines have also come under scrutiny. Many operators of small dams in the province have made deals to supply cryptocurrency businesses with cheap electricity directly, to the chagrin of state-owned power companies. Zhao Lei, general manager of a local State Grid subsidiary, said in May 2020 that such deals violate electricity market order, constitute tax evasion, and pose safety issues. A crackdown on illicit mines followed.

Another worry for Sichuan’s miners is the rising price of electricity. Despite the ambiguous stance of Chinese authorities, the lure of profits is still pulling people into Bitcoin. Competition has become fierce. “Last year, Aba’s electricity was cheap,” says Liu, the Bixin Mining CEO, referring to a Sichuanese region rich in hydropower. “But this year’s investment has overheated. The electricity price has increased a lot.” This year’s costs are 16% higher than last year, according to the Sichuan Power Exchange Center.

Many in the industry argue cryptocurrency businesses absorbing Sichuan’s excess hydropower are essentially green, using environmentally friendly electricity that nobody would have used otherwise. But the question is how long this argument will remain convincing if more miners are to stay in the province year-round. Four-fifths of Sichuan’s hydropower is of the run-of-the-river type, meaning the dam has no reservoir that can store water for dry spells. To meet power demand in drier winter months, the province generates up to about a quarter of its power from fossil fuels, and purchases electricity from other provinces.

This dynamic means hydropower is ultimately not the solution to the question of how to make Bitcoin environmentally friendly, says Alex de Vries, an economist and creator of website Digiconomist. In an article published 2019 in scientific journal Joule, he points out that seasonal variation of hydropower requires alternative energy sources, which in the worst-case scenario “presents an incentive for the construction of new coal-fired power stations to fulfill this purpose.”

Instabilities in electricity supply and demand, as well as climate change, also affect cryptocurrency mining operations outside winter. In May 2020, a delayed rainy season that reduced power production and caused higher-than-average temperatures that increased air conditioner usage meant electricity was diverted for residential use. Miners had no choice but to shut down temporarily. On Sunday, another power shortage forced the Sichuan government to ration power, again cutting off cryptocurrency mining businesses.

Rising electricity costs and policy uncertainties are driving mining operations abroad, Bixin’s Liu says, with investors setting their eyes on North America, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe.

But sentiments toward cryptocurrency mines are souring elsewhere too. Concerned about miners’ power use and carbon footprint, authorities in locales as varied as Iran, New York state, and Abkhazia, an autonomous region north of Georgia, have in recent months cracked down on illegal operations, proposed a moratorium on new mines, or banned the practice altogether, respectively. Citing the emissions caused by every transaction, electric car-maker Tesla said Wednesday it would no longer accept Bitcoin.

Li says he will move his operations to Sichuan for now, but he’s unsure what will happen when the province’s preferential policy expires at the end of next year. In the dry season, limited power resources will make competition fierce, he says.

“We estimated that this wet season would be the last good opportunity left for miners in China, and that afterward there will be more uncertainties,” Li says.

Source: Sixth Tone, 28 May 2021

Author: Li You